Erdoğan’s alliance with the Turkish nationalists at home resulted in the adoption of an aggressive foreign policy.

By Expert on modern Turkey

Introduction

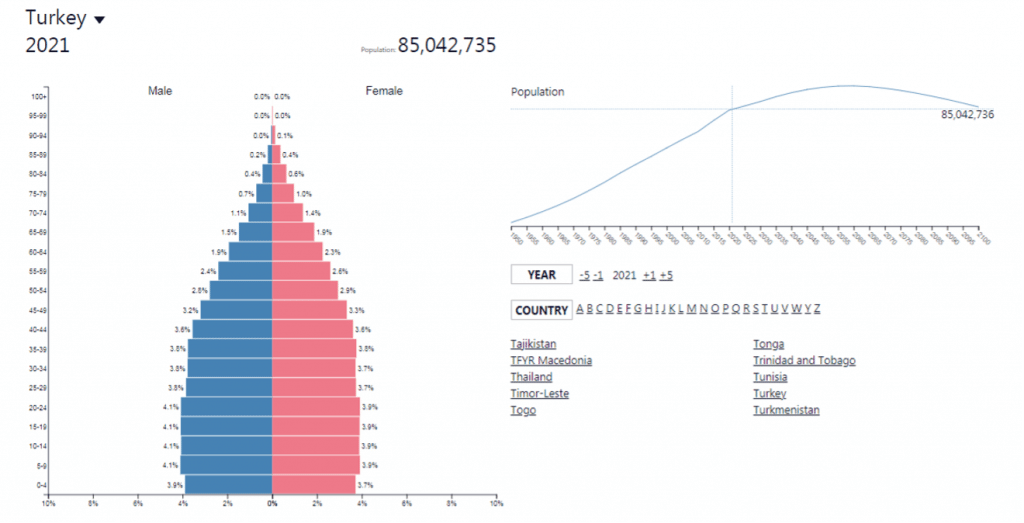

Turkey plays a crucial role in the Middle East mainly because of its strategic location, military and economic power, historical role during the Ottoman Empire, and its nearly 82.5 million population (July 2021 CIA World Factbook estimate). In recent years its society underwent a process of Islamization due to the Justice and Development Party (AKP). Turkey’s current president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the undisputed leader of the AKP, in power since 2002, also developed aspirations to lead the Muslim world. In parallel, Turkey’s foreign policy distanced itself from the West and became more assertive per its neo-Ottoman impulses.

Chapter One of this study reviews the centralization of power in the hands of Erdoğan. He successfully eliminated the limited checks and balances on the executive branch and changed the political system from parliamentary to presidential. He was first elected president in 2014. The Turkish army, once an important political actor whose task was to defend the secular republic, was progressively subordinated to civilian control. Erdoğan introduced changes to the judiciary to gain greater control of judicial appointments. The reforms in the education system – inserting Islamic content – has probably had the most significant impact on Turkish society.

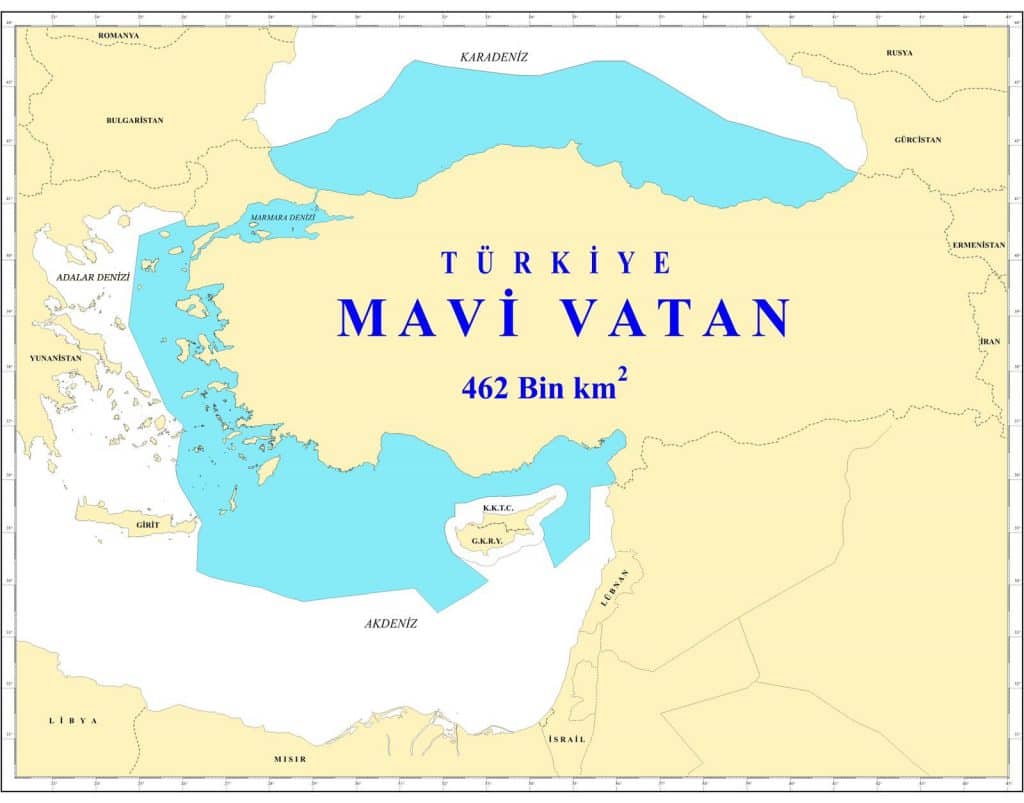

Chapter Two analyzes the ideological foundations of the irredentist Turkish foreign policy – the “Precious Loneliness” doctrine. According to this doctrine, Turkey should sacrifice its immediate short-term interests for the sake of bringing justice (Islamist ideology) to the lands where injustice (the lack of its Islamist ideology) exists by imposing Turkish-Islamic sovereignty or influence. Under Erdoğan, Turkey adopted a new naval doctrine called the “Blue Homeland” (Mavi Vatan), which rejects the status-quo that was established by The Treaty of Lausanne (1923), replacing it with Turkish maritime borders that expand into Greek and Cypriot territory. The treaty ended the Turkish War of Independence and turned the Ottoman Empire into the modern state of Turkey, without its former possessions that expanded across the region. As a result, the former parts of the Ottoman Empire gained independence and formed modern states. To implement this policy, Ankara decided upon an ambitious naval procurement program called MILGEM. However, unless Erdoğan delivers significant economic improvement, he will probably adopt additional authoritarian measures and challenge the West to divert the public’s attention toward historical, national, and religious matters.

Chapter Three reviews Turkey’s aggressive behavior across several theatres in the Greater Middle East, such as Iraq, Syria, the Aegean Sea, and Libya. The attempt to stymie Kurdish national aspirations is mainly motivated by military activities along Turkey’s border and domestic political needs. This chapter also reviews the tensions between Russia and Turkey and how Ankara has demonstrated restraint when facing a stronger power.

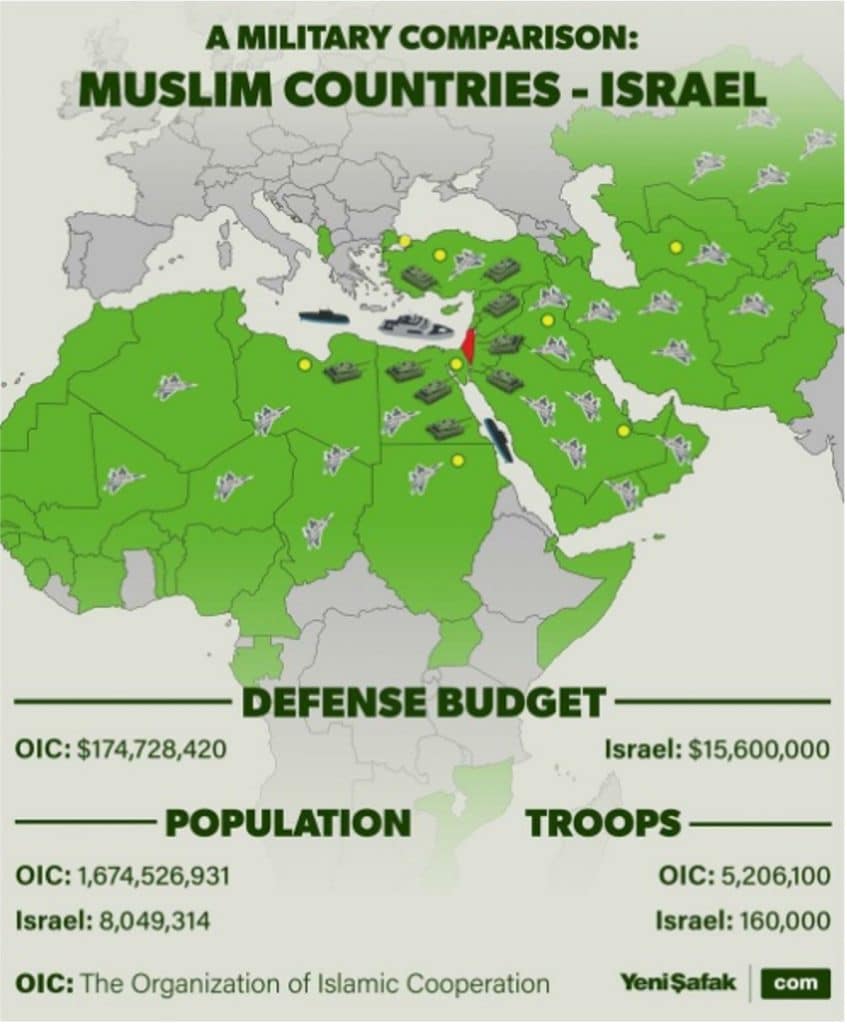

Chapter Four focuses on the growing enmity of Erdoğan-led Turkey toward Israel. It reviews the main areas of tension between the two countries: Iran, the Palestinians, and the Eastern Mediterranean. The deterioration in the bilateral relations (except for trade and tourism) strengthened the Israeli-Hellenic partnership.

Chapter Five offers policy recommendations for decision-makers in the West and Israel. Turkey’s greater assertiveness and outright military interventions beyond its borders require a careful and persistent policy for steering Turkey away from regional mischief. Its role in NATO needs to be reassessed. A balance should be reached in order not to lose Turkey to the Russia-China camp. The West and Israel’s main leverage on Ankara is in the economic realm that has become Turkey’s Achilles heel. Moreover, Erdoğan is leery of a confrontation with Washington. The West should also be aware of Turkey’s potential for nuclear proliferation.

The West should maintain close relations with the secular segments of the Turkish population and conservative pragmatist groups. However, a distinction should be made between Turkey’s current leadership and Turkish society to preserve the possibility of better relations with a future government that is not under AKP control. The planned 2023 elections are crucial for Turkey’s future. At this point, Erdoğan’s electoral victory is not assured.

Israel must exert considerable caution toward Turkey because it has no interest in turning this powerful country into an active enemy. Even under Erdoğan’s leadership, Turkey has demonstrated a certain degree of pragmatism regarding Israel. Jerusalem should emphasize that regional alignments such as the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) and the tripartite cooperation among Israel, Cyprus, and Greece do not seek to exclude Turkey. Israeli diplomatic activity on the Turkish issue must focus on Washington, seeking to harness the US to curb Erdoğan’s ambitions.

The challenge from Turkey requires rethinking several aspects of Israeli security strategy and intelligence priorities. Monitoring Turkish activity in Jerusalem and neutralizing its influence among the Muslim population should also be carried out.

This research project has been made possible by the generous support of Mary M. Boies. It also benefited from grants from Roger Hertog and Shlomo Werdiger. JISS thanks the sponsors of this far-reaching study.

Chapter One: The Trajectory of the Turkish Political System under Erdoğan

In Turkish political history, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is the most charismatic and influential figure after Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the republic.1 Erdoğan distinguished himself from the rest of his predecessors, having won every general election since 2002. His 19 years in power breaks Atatürk’s 18-year record (1920-1938). Unsurprisingly, the significant side effect of Atatürk and Erdoğan’s successes is authoritarianism.

Turkey has a political tradition of cult leader admiration going back to Ottoman empire days. The founder of modern Turkey, Atatürk, ruled Turkey with an iron fist. He closed two opposition political parties one after the other during his term of office. And indeed, he passed away in Istanbul’s Dolmabahçe Palace, a symbol of authoritarianism. So it is no surprise that Erdoğan is seeking to concentrate power in his hands like Atatürk and is building his palace in Ankara. For many Turks, assets like the presidential palace or Erdoğan’s “Air Force One” jetliner are acknowledged as signs of power and glory necessary for state power projection.

In contrast to Atatürk’s cultivation of a secular personality cult, primarily through the school curriculum, statues, and portraits, Erdoğan seeks to build his personality cult by neo-Ottoman and Islamist motifs. This is expressed through pharaonic infrastructure projects and architectural projects like mosques and monuments, as well as through cardinal Islamic reforms in the education system, state structure, army, judiciary, and the elimination of the principle of separation of powers.

Erdoğan is explicit about this. On the eve of the foundation of his Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2001, he publicly stated that under his party’s rule, “nothing will be the same in Turkey anymore.” He has kept his promise.

The Elimination of Checks and Balances

At first, in 2003, capitalizing on the European Union accession process, Erdoğan launched a campaign to weaken the influence of the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) in the National Security Council. He changed the composition of this body by ensuring a civilian majority. In 2007, he further strengthened his position vis-à-vis the military when he did not comply with the military’s infamous “e-memorandum” that asked the AKP to withdraw the candidacy of Abdullah Gül for the presidency. As a result, Gül became Turkey’s eleventh president in 2007. Erdoğan also managed to take control of the office of the presidency. This allowed Erdoğan to overcome a significant obstacle in the decision-making process since Turkish presidents can veto parliamentary legislation, as did former President Ahmet Necdet Sezer (2000-2007), opposing Erdoğan’s plans for constitutional reforms and changes on the headscarf question.

After seizing complete control of the executive branch of government, Erdoğan took bolder actions, such as launching a peace process with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in 2009, supported in the rural Kurdish periphery. Thus, the Kurdish political movement became Erdoğan’s undeclared ally. However, to avoid being tagged as a traitor by nationalists, he did everything possible to pursue the peace process with the Kurds semi-secretly, using the country’s intelligence agency.

Erdoğan also moved to take control of the judiciary. Following the 2010 referendum, which narrowed the jurisdictional reach of military courts, he also changed the structure of the Constitutional Court and Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors,2 becoming a key player in nominating judges and prosecutors.

The year after, the government pursued mass arrests against military personnel in the framework of the Ergenekon probe. As a result, then-Chief of Staff Işık Koşaner and the generals of the ground, naval, and air forces offered their resignations in protest. Erdoğan seized this opportunity to further cement his grip on power by accepting their resignations. Erdoğan then appointed the head of the gendarmerie, General Necdet Özel, to the post of the Chief of Staff. This was unprecedented since traditionally, this post belonged to the ground forces. Indeed, the immediate results of this decision were seen when Erdoğan took control of the Supreme Military Council (YAŞ), sitting demonstratively at the head of the table without the chief of staff. This significant political victory allowed him to continue to de-emphasize the political role of the military.

In 2012, Erdoğan removed the course “National Security Knowledge” from the curriculum in the education system. The course was first introduced into the curriculum in 1926. Apart from “preparing the Turkish youth to serve in the army,” its main task was to legitimize the army’s role in the nation’s decision-making process. This move obliterated the TSK’s most important mass indoctrination vehicle in persuading the Turkish people of the “the necessity of having the TSK” in the decision-making process.

Erdoğan moved to accumulate yet more power in his hands. He initiated a discourse favoring the transformation of Turkey’s parliamentary system into a “Turkish style” presidential system, lacking strong checks and balances. This radical change was criticized harshly by opposition circles and by Erdoğan’s comrades like then-President Abdullah Gül.

The most significant response to such expanding authoritarianism occurred in the Gezi Park protests in 2013, which started as a small protest to preserve Istanbul’s tiny Gezi Park. Within days the modest environmental protests turned into massive nationwide rallies against the authoritarianism of the Turkish premier. In addition, a December 2013 probe of corruption in AKP circles raised additional concerns.

The Road to a One-Man System

On March 13, 2014, the Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP), which was supposed to support Erdoğan for the continuation of the peace process with the PKK, made a critical U-turn and declared the party’s opposition for Erdoğan’s presidency. Nevertheless, Erdoğan won the March 2014 municipal elections, and on August 10, 2014, became the first popularly elected Turkish president. Before that, the presidency was merely a symbolic post lacking political clout. But Erdoğan decided to implement the Russian “Putin-Medvedev” style of governance, allowing him to run the country with “power of attorney” through the office of the Prime Minister. Ahmet Davutoğlu became his first partner. However, given the relative failure in the June 2015 elections where the AKP won only a plurality,3 and the fact that Davutoğlu refused to act as Erdoğan’s “yes man,” Erdoğan replaced Davutoğlu in 2016 with his close associate Binali Yıldırım (a politician without charisma).

In the aftermath of the June 2015 elections, Erdoğan faced the “betrayal” of the HDP and the violence between the PKK and Turkish security forces. This led Erdoğan to ally with the ultra-nationalist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). The alliance heralded an end to the peace process. Moreover, it indicated the adoption of “hard-power” based foreign policy, stressing the importance of military operations in determining facts on the ground.

The failed coup attempt on July 15, 2016, facilitated this agenda. While blaming his rival Fethullah Gülen for orchestratıng the coup attempt from the US, Erdoğan used nationalism and anti-Americanism to consolidate more power in his hands. Apart from organizing mass rallies, he declared a state of emergency, acquiring executive powers like issuing statutory decrees, which mostly eliminated his reliance on Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım.

Further, Erdoğan decided to strengthen his alliance with Turkish nationalists. He launched a purge of the state bureaucracy, replacing many bureaucrats with personnel more nationalist and loyal to the government. The partnership with MHP was further strengthened when Erdoğan began to de-legitimize the Kurdish HDP and its political leaders Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ. On November 4, 2016, this defamation campaign reached its peak when the two Kurdish political leaders were arrested and taken to prison.

Moreover, Erdoğan launched three military operations in Syria along the border: Euphrates Shield (2016), Olive Branch (2018), and Peace Spring (2019). These campaigns sought to remove the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and Syrian Kurdish People’s Defense Units (YPG) militia elements along the border, rally people around the flag, and boost nationalism. As a result, Erdoğan managed to put a wedge between the Kurdish HDP and the rest of the political parties.

Erdoğan decided to use military and religious matters to increase his public approval. The military activities diverted public attention from the deteriorating economy. Therefore, Turkey’s military intervention in Libya, its brinkmanship policy vis-a-vis Greece and Cyprus, Ankara’s decision of turning the Hagia Sophia Museum into a mosque, and its support to Azerbaijan in its war against Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh – all can be seen as part of his domestic survival campaign.

Fragmented Society and the Politics of Alliances

The most important step in Erdoğan’s journey for political survival took place on April 16, 2017, when he led his country to a constitutional change – moving away from a parliamentary system and adopting a presidential one. It was a narrow victory. He enjoyed the results of the 2017 referendum only after the presidential elections of June 24, 2018. As soon as he took the presidency, he began to usurp parliament’s legislative responsibilities by issuing presidential decrees. Despite parliament’s erosion of power, Erdoğan still needs most of the parliament to pass laws.

Realizing AKP’s inability to receive more than 50% of the votes before the 2018 elections, Erdoğan paved the way for drastic reform in the elections law. As a result, political parties could engage in alliances to prevent elimination if they did not pass the 10% national threshold. This saved AKP partners, such as the MHP. Moreover, other political parties such as the small nationalist Grand Unity Party (BBP) could also contribute to the AKP by forming an alliance and helping gain a majority in parliament. Indeed, the AKP, MHP, and the BBP formed the “People’s Alliance” (Cumhur İttifakı – Cİ). Seeing this challenge, the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the nationalist İyi Parti (The Good Party) formed the “Nation’s Alliance” (Millet İttifakı – Mİ).

In order not to create a rift within the Mİ, the Kurdish HDP refrained from officially supporting this block, allowing the nationalist İyi Parti to remain with the Mİ. Yet, while acquiring unprecedented power in his hands, Erdoğan created a situation where his position became more vulnerable. The new rules of the game, developed by Erdoğan, generated the possibility of establishing an anti-Erdoğan bloc.

The most crucial test of the new political reality was the March 31, 2019, municipal elections, where he was defeated. Erdoğan’s candidates in the capital Ankara and in Istanbul lost to CHP’s Mansur Yavaş and Ekrem İmamoğlu, respectively. The informal Kurdish HDP’s support was key to the Mİ opposition bloc. Despite the fragility and profound disagreements among the parties within the Mİ, it defeated Erdoğan’s Cİ alliance.

What Are Erdoğan’s Options?

Will Erdoğan accept the results of the 2023 general elections if defeated, or will he seek to remain in power at all costs? This question is being widely discussed. It seems that Erdoğan is preparing himself for both options. On the one hand, he seeks to achieve victory at the ballot box with an aggressive political campaign that has continued in full strength despite the coronavirus crisis. But, on the other hand, he also has formed armed formations called “Takviye” (Reinforcements) and “Bekçi” (Night-watchmen) that are loyal to him.

Turkey’s president knows that to stay in power by political means, he must crush the Mİ so that the “Istanbul and Ankara municipal election disasters” will not repeat themselves in the 2023 general elections. Therefore, Erdoğan seeks to inflict deep wounds among the parties of the Mİ by forcing them to respond to various scenarios. For instance, Erdoğan has appointed government trustees (“Kayyum”) to eliminate the Kurdish HDP-affiliated mayors in eastern and southeastern Turkey, legislated a new constitution to address the definition of Turkishness and Turkish citizenship, and passed legislation regarding relations between religion and state.

These issues have not produced the desired rift between the nationalist İyi Parti and the Kurdish HDP. Erdoğan still seeks to steal İyi Parti’s nationalist constituency by forcing the İyi Parti to side with the Kurdish HDP publicly. The Cİ annulled the parliamentary membership of Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu – a member of HDP in parliament who is a well-known human rights defender – due to a two-and-a-half-year prison sentence handed down to him on “terrorism charges.” Despite the accusations against Gergerlioğlu, the İyi Parti stood up for the HDP member of parliament and openly condemned the steps taken against him.

Apart from the Kurdish question, Erdoğan seeks to set Mİ-affiliated parties against one another by opening a debate on gender and politics. This time, the focus of Erdoğan’s attention was focused on the possible rift between the secularist and the conservative circles within the Mİ camp. On March 20, 2021, Erdoğan declared his country’s unilateral withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention, an internationally binding document to defend women’s rights.4 Such a step requires a parliamentary decision according to the Turkish constitution. Despite this, given the destruction of the separation of powers, Erdoğan’s arbitrary decision remains in force. This act was another massive blow for Turkish democracy.

Erdoğan also has engaged in gerrymandering to sway election results. For instance, on March 21, 2021, Erdoğan unilaterally changed the borders of the province of Diyarbakır by moving the Şenyayla area of the Kulp district to the jurisdictional authority of the Muş province.5 In addition, it seems that by adding Kurdish voters to Muş’s pro-AKP regions, Erdoğan seeks to weaken the Kurdish party in the Diyarbakır province.

Another act was the nomination of the Turkish Central Bank chairmen. To put an end to the Lira’s devaluation versus the US Dollar (peak: 1 Dollar = 9.75 Liras, in October 2021), both previous chairmen of the Turkish Central Bank (Murat Uysal and Naci Ağbal) sought to increase the interest rate. However, both were fired in succession. Today the current chairman of the Turkish Central Bank is Şahap Kavcıoğlu. According to reports in the Turkish press, Kavcıoğlu is associated with Erişah Arıca, the controversial Ph.D. supervisor of the former finance minister – Erdoğan’s son-in-law Berat Albayrak. Kavcıoğlu’s refusal to raise interest rates, and the adoption of the failed economic policies of Albayrak, indicates the Central Bank’s lack of independence.6

The negative effect of COVID-19 on the Turkish economy has been felt especially in the tourism and aviation sectors. Given the high cost of living, the economy appears to be the most significant challenge Turkey faces. Turkey’s relatively young population lacks employment. With unemployment at 13.4% and rising,7 Erdoğan needs to improve the situation as soon as possible.

If the main opposition parties unite against Erdoğan and support one candidate to challenge him (this would most likely be the Mayor of Istanbul, Ekrem İmamoğlu), Erdoğan would be seriously challenged. Opposition parties, including those that originated in the AKP, could join. This could include the Solution Party of Ali Babacan and the Future Party of Ahmet Davutoğlu. But the former presidential candidate of CHP, Muharrem İnce, may run independently and split the opposition bloc – playing into Erdoğan’s hands. Having seen this as an opportunity, Erdoğan recently opened a new public debate on lowering the national threshold from 10% to 3% or 5% to create a rift within the ranks of the Mİ, which would facilitate the smaller parties (Davutoğlu, Babacan, and others) to leave the pact against him.

The 2019 Istanbul municipal elections smashed Erdoğan’s invincibility. If the unwritten so-called Turkish political rule that “whoever wins in Istanbul and Ankara will govern Turkey” is still valid, then Erdoğan could be defeated in the 2023 elections. However, after governing Turkey for 19 years, Erdoğan distinguishes himself from his predecessors in that he has turned his political party into “the state itself.” Therefore, in case of an electoral defeat, Erdoğan is unlikely to accept the results of the elections and insist on repeat elections, as he did in Istanbul. Moreover, since he already has formed his own militias (the Takviye and Bekçi forces), Erdoğan may be planning to seize power altogether.

If Erdoğan steps down, his successor would have to adopt similar practices and may choose to purge Erdoğan’s supporters in the police, army, intelligence services, government ministries, and other governmental bodies like the Directorate of Religious Affairs (which has spearheaded Erdoğan’s Islamization campaign). But even if this kind of purge takes place, the impact of Erdoğan’s religious policies on Turkish society and government would persist.

Turkish foreign policy also has been affected by Erdoğan’s emphasis on religious motifs. Especially since the adoption of the “Precious Loneliness” foreign policy doctrine, Ankara’s eagerness to create diplomatic frictions with non-Muslim states (like Israel, Greece, Cyprus, Armenia, Holland, Germany, Russia, China, the United States, and the European Union) suggests a pessimistic picture for the future. Despite US President Joe Biden’s open call for supporting Erdoğan’s adversaries in Turkey, the US and EU will not influence political trends in Turkey unless they employ tough economic sticks and carrots.

Given US support to the Kurdish PYD-YPG in Syria and its sheltering of Fethullah Gülen (considered by Erdoğan as the mastermind behind the failed coup attempt) and given the EU’s unconditional support to Greece and Cyprus in the Eastern Mediterranean against Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots – it seems that both the US and EU will continue to be viewed with suspicion by large tracts of the Turkish public.

In conclusion, unless Erdoğan delivers significant economic improvement, he probably will adopt additional authoritarian positions. He also may challenge the West to divert the Turkish public’s attention towards historical, national, and religious matters. This will help Erdoğan cover up possible failure at the ballot box in 2023 and aid in his bid to remain in power.

Chapter Two: Foundations of Turkish Irredentist Policy

Introduction

Unlike the imperialist Ottoman Empire that expanded its territory through conquests, modern Turkey under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk refrained from adopting an expansionist foreign policy. Instead, Atatürk’s famous motto, “peace at home, peace in the world,” guided Turkish foreign policy, which accepted the territorial status quo and refrained from intervening in the internal affairs of other countries.

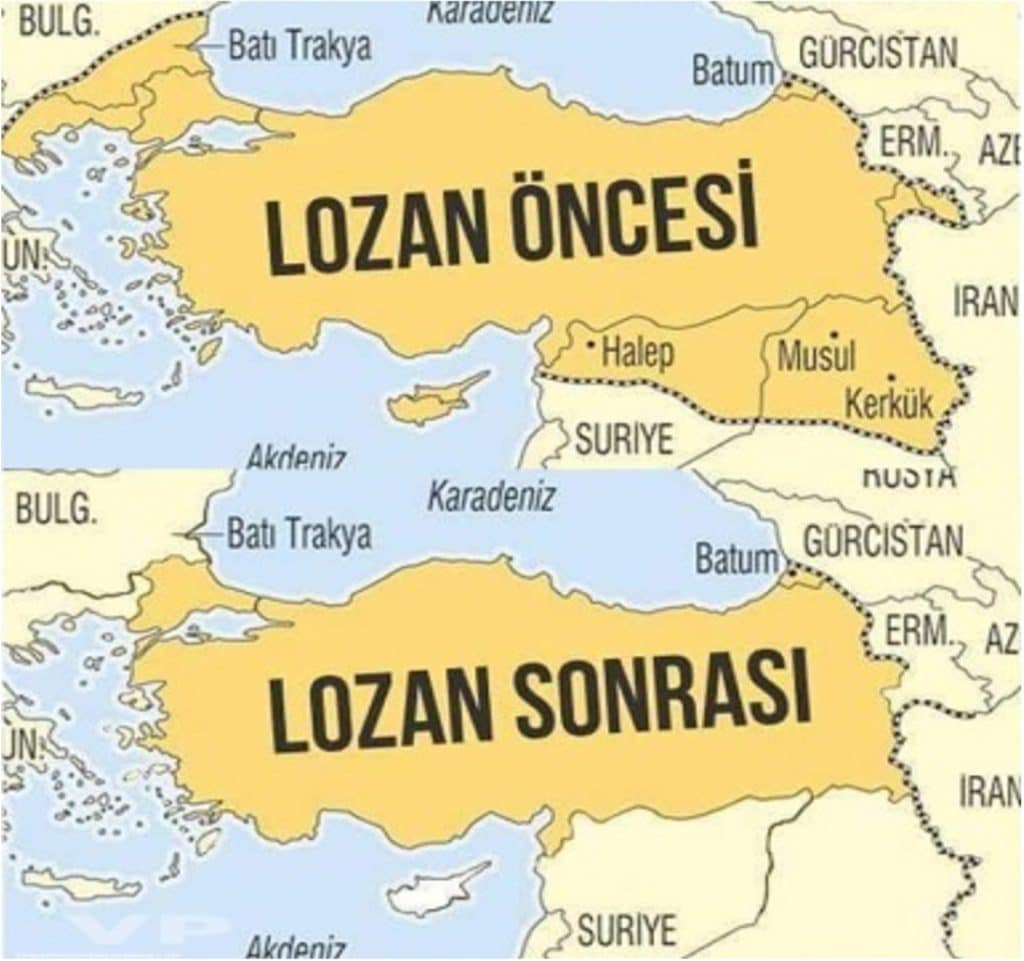

The Treaty of Lausanne was acknowledged as a diplomatic victory because it annulled the Treaty of Sevres (1920) that intended to remove Turkey from Europe and reduce Turkey’s territory to a small portion of land in central and northern Anatolia. The erection of the Lausanne Peace Treaty Monument in the city of Edirne in 1998 (by then Turkish President Süleyman Demirel) indicates the great significance attributed to this treaty by Turkish governments.8

However, Turkish leadership under Erdoğan has rejected the Lausanne Treaty’s historical importance in recent years and adopted an irredentist policy. This chapter reviews the ideological underpinnings of this policy, its economic burden, its support in public opinion, and emerging nuclear ambitions.

The Ideological Underpinnings of Irredentist Policy

The rise of Neo-Ottomanism – which initially appeared during the term of former Turkish president Turgut Özal (1989-93) – eroded the Lausanne Treaty’s reputation and led to statements in favor of its repudiation. The Ottoman glory and its most striking manifestation, the map of the expanded Ottoman Empire, which projected Turkish sovereignty from the Balkans to the Middle East and North Africa, overshadowed the Lausanne map. Moreover, the Neo-Ottomanists forgot the war-weary mood of Turkish leadership that signed the Lausanne agreement.

Since the formation of the political alliance between Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) in November 2015, Erdoğan’s Neo-Ottoman tendencies became intertwined with Turkish nationalism. Especially after the failed coup attempt in July 2016, this synthesis helped Erdoğan mobilize the masses.

The blueprint of this worldview could be detected in Erdoğan’s speeches that later transformed into military actions in places such as the Eastern Mediterranean, Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Nagorno Karabakh.

Perhaps Erdoğan’s most revealing speech was delivered on September 29, 2016. For the first time, Erdoğan termed the Lausanne Treaty as a defeat, explaining that it failed to secure control of the Greek islands, such as Kastelorizo, located close to the Turkish coast and that was given to Greece.9 Erdoğan portrayed the Lausanne Treaty as a slightly upgraded version of the despised Sevres Treaty. Erdoğan raised the issue to stoke Turkish nationalism and the nation’s “Sevres Syndrome,” a fear of dismemberment of the state by hostile Western powers.

Erdoğan suggested improving Turkey’s situation by adopting an irredentist foreign policy – the “Precious Loneliness” doctrine. Per this doctrine, Turkey should sacrifice its immediate short-term interests for the sake of its Islamic moral values that are based on the “Ideal World Order” (Nizam-ı Alem Ülküsü). The “Ideal World Order” seeks to bring justice to the world by imposing Turkish-Islamic sovereignty in lands where injustice exists and the “oppressed” suffer. Indeed, in another speech on December 31, 2017, Erdoğan emphasized the loss of 18 million sq. km. from the territory of the Ottoman Empires to 780 sq. km. (Turkey’s current borders). These themes were commonly voiced in Turkish discourse.10

Moreover, this worldview has been officially embraced by Erdoğan’s nationalist allies: the nationalist Great Unity Party (Büyük Birlik Partisi) and its youth wing “Alperenler Ocağı” (Turkish-Islamic Warriors Hearths); and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and its youth organization “Ülkü Ocakları,” (“Idealist Hearths”), also known as the Gray Wolves.

Contemporary Turks were reminded of the Ottoman parliament’s last decision, the “National Pact” (Misak-ı Milli – 1920), that drew the borders of the homeland from the Chalkidiki peninsula of Greece in the west to Mosul, Kirkuk, and Aleppo. Pro-government segments of society embraced this revisionist vision. In addition, the Pan-Turkic “Red Apple” (Kızıl Elma) ideal that seeks to unite all Turkic people under one leadership to reach a defined objective such as conquering territory became a popular topic in Turkish politics.11

This discourse paved the way for an irredentist foreign policy. In this regard, Turkey’s military operations beyond its borders in Iraq and Syria and the presence of the TSK in those newly captured territories to create defensive borders – are in line with the Ottoman parliament’s “National Pact” (Misak-ı Milli) decision. Moreover, these steps were taken in the south, and the Turkish government also seeks to increase its influence in the Western Thrace region of Greece where the Muslim Turkish ethnic minority lives in the cities of Xanthi (İskeçe) and Komotini (Gümülcine).

Indeed, Erdoğan publicly asked his Greek counterpart Prokopis Pavlopoulos during his visit to Athens in December 2017 to make amendments to the Lausanne Treaty. His goal was to increase his influence in the Turkish diaspora in Greece and define their status as “Turkish” instead of part of the Greek Muslim community. Erdoğan also asked Pavlopoulos to grant the Muslim community of Western Thrace the right to elect its own religious leader.12 Erdoğan probably sought a role in this region for the Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet).

The Turkish president also asked his Greek counterpart to find a “just” solution to the Aegean Sea continental shelf issue.13 Athens seeks to address this question in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS, 1982). However, Turkey did not sign this convention and sought to persuade Greece to accept its “just solution,” which aimed to draw a median line between the Turkish and the Greek mainland. Such a scenario disregards the continental shelf rights of the Greek islands and turns them into Greek enclaves in Turkish waters.

All of Erdoğan’s requests were rejected by Athens. Moreover, Greece signed an agreement with Italy, Cyprus, and Israel to build a gas pipeline transferring energy from the Eastern Mediterranean to Europe, ignoring Turkey’s aspiration to be the energy bridge to Europe. Turkey then adopted a brinkmanship policy based upon a new naval doctrine called the Blue Homeland (Mavi Vatan). Developed by admirals of Turkey’s navy, who were aware of the strategic importance of the sea, this approach is influential among Turkey’s military, political, economic, and intellectual elites. This military posture advocated by the navy also rejects Lausanne borders, replacing them with Turkish maritime borders at the expense of Greek and Cypriot sovereignty.

In November 2019, the Blue Homeland doctrine was implemented by signing a maritime delimitation agreement over the Exclusive Economic Zone with Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA). This bold step severed the maritime contiguity between Athens and Nicosia and implied the Turkish ability to block the planned gas pipeline from the Eastern Mediterranean to Europe. Turkey also intervened militarily in the Libyan civil war. Greece, Cyprus, and the EU perceive these actions as aggressive behavior. Erdoğan nevertheless stated that his country would not bow down to a “new naval Sevres.”14 Instead, Erdoğan drew the “Sevres” card again, seeking to rally his people around the flag to challenge Greece and Cyprus.

Under the Blue Homeland doctrine, Erdoğan implemented an ambitious naval procurement program called MILGEM. Ankara has produced four well-equipped warships: TC-G Heybeliada, TC-G Büyükada, TC-G Burgazada, and TC-G Kınalıada. These four corvettes can evade radar detection and are known as “the ghost ships.” On October 18, 2018, these Turkish vessels were dispatched to the Eastern Mediterranean to conduct “demonstration of power” missions and engage in “maritime dogfights” with the Greek navy. In October 2019, Turkey began to build its first submarine (MILDEN), which is supposed to become operational in 2030.15 Turkey also has started building its first aircraft carrier, the “Anadolu” (Anatolia). At first, Anadolu was designed to host F-35 jets. However, in April 2021, the US disqualified Turkey from the F-35 program, so Turkey turned the Anadolu into Turkey’s first Bayraktar UAV carrier.16 The fact that Bayraktar UAVs and the Anadolu ship are “made in Turkey” significantly contributes to Erdoğan’s public approval (alongside strong criticism regarding the loss of the F-35s).

The Economic Dimension

After 19 years in power, Erdoğan’s public approval has begun to erode. The most significant reason for this is the steady deterioration of the Turkish economy. The unprecedented devaluation of the Turkish Lira versus the US dollar appears to be the most striking indicator of this negative trend. When Erdoğan’s AKP came to power in 2002, one dollar was equal to 1.68 Turkish Liras. Since the Gezi Park protests started in May 2013, the Turkish currency has been in free fall. In October 2021, the currency reached an all-time low of 9.75 Liras.

The core reasons for this deterioration are Turkey’s departure from the Western political bloc, growing Turkish authoritarianism, lack of confidence in the judiciary, the rise of nepotism and arbitrary decisions, extraordinary events like the failed coup attempt, and Erdoğan’s continuous intervention in the Turkish Central Bank’s monetary policy.

Despite this negative economic picture, Erdoğan’s ambitious interventionist policies continue in various theatres such as the Eastern Mediterranean, Syria, Iraq, and Libya. As a result, Turkey’s defense budget also has steadily grown. The 2021 budget of the Turkish Defense Ministry was 138 billion Liras.17

Turkey’s Military Expenditures under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

| 13641 | 15426 | 15568 | 16232 | 18622 | 19528 | 21878 | 24873 | 26526 | 28485 |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| 31779 | 35082 | 38467 | 42619 | 53853 | 64243 | 94860 | 117089 | 124480 | 138000 |

In short, over the past decade, Turkey’s military expenditures have grown by 86% (nominal value).20 As a result, defense expenditure as a percentage of the gross domestic product rose from 2.3% to 2.8%.21

The Lira’s devaluation versus the dollar has led to a decrease in the defense budget from $18.63 billion to $17.7 billion. The reduction in the defense budget in dollar terms does not reflect a policy change but rather highlights the decline in Turkey’s purchasing power abroad.

The devaluation of the Turkish Lira inevitably affects Turkey’s attitude, especially towards its mercenaries that act on its behalf abroad. For instance, during Operation Euphrates Shield in 2016 that had Turkish forces enter Syria, Turkey paid a monthly salary of $300 in Turkish Liras to Syrian mercenaries. However, at the beginning of 2019, this sum declined to $100, with payments made once every two months.22 According to Turkish opposition newspaper sources, Syrian mercenaries expressed their discontent and asked to receive their monthly wages in Syrian Pounds.23 While the salaries in Syria were relatively low, wages in other theatres such as Libya and Nagorno Karabakh of southwestern Azerbaijan were higher. Accordingly, the monthly income of a Syrian mercenary can reach $1,200,24 while the salary in Nagorno Karabakh reached $1,500.25 The higher wages of these Syrian mercenaries were most probably paid jointly by Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Despite these salaries, Turkey adopted a more stringent payment policy regarding its own personnel. The monthly salary of Turkish conscripts who do not serve in the country’s eastern provinces is 145 Liras, only $15, while those who serve in the eastern provinces must cope with the separatist PKK and receive 1,216 Liras, or $126. This allows Erdoğan to pursue an interventionist foreign policy on the cheap.

In addition, Turkey’s war machine is actively supported by Qatar. Doha increased its investments in Turkey to $6.3 billion as of 2019 and did not conceal its appetite for control of TSK military equipment factories. For example, it bought Turkish tank track production facilities, causing an uproar among opposition parties.26

Further, Qatari penetration into the Turkish economy is not limited to the military. Doha has invested in high-value real estate and the banking, media, fashion, and automotive sectors.27 In addition, in the framework of swap agreements in 2018 and 2020, the Qatari national bank provided $15 billion to the Turkish Central Bank.28 Thus, Qatar eases the burden on the Turkish economy that must bear Turkey’s interventionist policies.

Public Opinion

Apart from relatively low expenditures and Qatari financial support, what also enables Erdoğan to pursue an interventionist foreign policy is a lack of any serious public opposition.

Indeed, the Turkish public perceives the TSK’s military presence in twelve different countries (including Cyprus, Syria, Iraq, Somalia, Qatar, and until recently, Afghanistan) as the price to pay for becoming a global power like the United States. Turks have dreams of grandeur and of reviving the Ottoman Empire.

Some of the Turkish public perceived TSK casualties on various fronts as not getting the respect and recognition from the government that they deserved. In addition, Turkey’s anti-individualist, collectivist approach towards its soldiers (which portrays each casualty as a statistic in the quest for global influence, rather than an individual with a name and surname) allows the Turkish government to take warlike decisions without facing significant societal pressure

Two crucial cases demonstrate this reality. In 2016, ISIS burnt two Turkish soldiers alive, and in 2021, the PKK executed 13 Turkish soldiers held as prisoners of war. Yet, during their captivity, no Turkish non-governmental organization launched a public campaign to force Ankara to reach a prisoner swap with ISIS or the PKK. On the contrary, after the execution of the Turkish soldiers, TSK’s retaliation was emphasized rather than the personal tragedies of the fallen soldiers. This policy reached its peak when it was directed against the Kurdish PYD (that is equated with the PKK) in Syria. Thus, the PKK-PYD nexus’s existence limits the opposition’s maneuvering capability in criticizing the government’s interventionist policy.

While Erdoğan achieved a national consensus for its military campaigns against the PYD-PKK in northern Syria, he failed to secure similar support for Turkey’s intervention in Syria’s Idlib province. In February 2020, when 34 Turkish soldiers were killed due to a Syrian air attack (with reported Russian participation) at Balyun, a public outcry damaged the government’s public approval rating.29 However, right after this incident, the government deflected public pressure by launching Operation Spring Shield against Syrian President Bashar Assad’s forces (while overlooking the Russian connection). Instead of covering the Balyun incident, the government-controlled media began to cover the Turkish retaliation mission against Assad’s forces while praising the TSK for its usage of its Bayraktar UAVs. As a result, the slain 34 soldiers turned into a marginal statistic, and the government once again managed to boost Turkish nationalist sentiments.

This policy also caused growing xenophobia against Syrians in Turkey. Apart from launching Operation Spring Shield, the Turkish government also decided to push Syrian and Afghan refugees towards the Greek border to force the EU to intervene in Idlib in favor of Turkey against Russia. This dramatically decreased public pressure on the government and turned the Greek government into the core culprit for the “humanitarian disaster” at the border. After the eruption of COVID-19, Turkey was forced to pull back and resettle these refugees in repatriation centers.)

Nuclear Infrastructure

Turkey also took significant action in the field of nuclear energy. Turkey is dependent on imported natural gas and oil. However, the country’s growing need for power has steadily increased energy expenditures. Therefore, Turkey has decided to decrease dependence on foreign energy suppliers by starting its nuclear energy program. However, Turkey will still be dependent on Russia since Moscow will be the supplier of nuclear fuel.

Turkey plans to construct three nuclear reactors in Akkuyu (Mersin), Sinop, and İğneada. Turkey signed agreements with Russia and a Japanese-French consortium to build four VVER-1200 units in Akkuyu and Sinop. Erdoğan’s government plans to start the operation of the Akkuyu reactor during the republic’s centenary celebrations in 2023.30 In 2014, the Japanese Asahi Shimbun newspaper reported that the uranium enrichment and plutonium extraction activities might pave the way for Turkey to develop a nuclear weapon.31 Moreover, in September 2019, Erdoğan accused Israel of possessing nuclear weapons and asked why Turkey should refrain from acquiring nuclear weapons if other states have such weapons. On September 30, 2021, in the aftermath of the Turkish president’s Russia visit, Erdogan announced the Russian-Turkish partnership to construct the second and third reactors – bypassing the Japanese option.32

Turkey’s missile-launching capabilities also should be examined. Turkey successfully produced two short-range ground-to-ground missiles called “Bora” (250 km. range) and “Yıldırım” (150 km.). However, Turkey could only use its potential nuclear military capability against its neighbors without a long-range missile program.

Ankara has also decided to launch a “Turkish Space Program,” which includes missiles capable of putting satellites in orbit. In fact, on December 13, 2018, Turkey started its space program with a presidential decree, which President Erdoğan made public in February 2021. Furthermore, in 2021 the Turkish Defense Industries Directorship (SSB) signed a cooperation agreement with the domestic rocket manufacturer Roketsan for launching a micro-satellite. Finally, in August 2020, Ankara launched into space its first homemade rocket. Turkey has received assistance in this regard from Kazakhstan and Elon Musk’s SpaceX project.

Turkey’s advances in nuclear and missile technologies strengthen Turkey’s image as a great power and encourage further adventurism.

Conclusion

After 19 years in power, President Erdoğan is aware of his domestic political vulnerabilities. The deteriorating economic situation has led him to divert the attention of the masses from financial difficulties toward religion and nationalism. Therefore, he preys upon the basest nationalist impulses of the Turkish public to bolster his political future. His emphasis on the Sevres Syndrome and the National Pact paved the way for an attack against the Lausanne Agreement’s legitimacy. This caused a deterioration in relations with Greece, which led to adopting the Blue Homeland doctrine that expands the “Sevres syndrome” from the land to the sea. Moreover, his political alliance with the Nationalist Movement Party also pushed Erdoğan to take bold actions against the Kurds in Syria and Iraq.

Relative success in these theaters later encouraged Turkey to act beyond its borders and even led it to intervene militarily in Libya and (indirectly) in Nagorno Karabakh. These military campaigns require financial resources, for which Turkey recruited Qatar as a financial backer.

Despite growing economic difficulties and increasing dependency on Qatar, Turkey continues to act ambitiously throughout the region, particularly in the Eastern Mediterranean. A burgeoning military-industrial complex sustains Turkey’s ambitions. Turkey has made giant steps to strengthen its navy and even launched a nuclear and ballistic missile program integrated into its space program.

Turkey’s military interventions in the region, its purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defense system (after not being able to purchase the American Patriot system), and its continuous antagonist foreign policy vis-a-vis some members of NATO raise grave concerns.

Chapter Three: The Contours of Turkish Interventionism

Introduction

Over the last decade under Erdoğan, Turkey has become an increasingly active player in the greater Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean. At the beginning of this period, Turkey’s policies mainly were in “soft power.” However, after the failed coup attempt, this posture was replaced by a belligerent, interventionist, irredentist foreign policy emphasizing “hard power.”

The shift from a soft power-based Turkish foreign policy to a hard power-based approach has had significant consequences for countries in the region. Turkey’s neighbors which it has troubled relations include Iraq, Syria, Greece, and Cyprus. Moreover, for the first time since the foundation of the modern state, Turkey has gone beyond its traditional geopolitical areas of influence and intervened militarily in Libya.

Given its success on the ground, Ankara now swaggers with self-confidence. Consequently, Turkey does not hesitate to challenge NATO allies such as France and Greece, let alone its adversaries. This chapter reviews Turkey’s aggressive behavior across several theatres and the circumstances under which Turkey may have to adopt restraint.

Iraq

After the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, Turkey was apprehensive about developments, particularly the impact upon the Kurds. It was concerned about the emergence of a Kurdish state. While Turkey managed to reach a bearable modus vivendi with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), it feared how the invasion would influence Kurdish nationalist energies among Kurds living in Iraq, Syria, and particularly Turkey.

Already in May 2019, with the start of Operation Claw, Turkey signaled its intention to change the strategic landscape in Iraq by implementing a different approach in its long war against the PKK. The goal of the PKK has been the establishment of an “independent united Kurdistan” within the geographical boundaries of Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Turkey. Unlike what occurred during 33 previous military raids in Iraqi territory since 1983, in Operation Claw, TSK stationed troops in northern Iraq. By establishing “temporary” army bases, the TSK established a security zone where it confronts and limits the activities of the PKK within Iraqi territory, turning northern Iraq into an active combat zone. As a result, many Kurdish villagers in northern Iraq were forced to leave their homes, and their fields were burned, destroying many livelihoods.

Turkey’s pressure on the Kurds reached a new peak on June 5, 2021, when Ankara decided to launch an airstrike against the Makhmour refugee camp in Iraq, killing PKK senior member Selman Bozkır and two other militants. Since its establishment in 1998, Turkey considered the Makhmour camp a significant recruitment base for the PKK. In a June 1 speech, President Erdoğan equated Makhmour with the PKK’s headquarters in the Qandil Mountains.33 Erdoğan’s statement was alarming because he compared a well-known civilian refugee camp with the PKK’s operations center.

The West did not embrace the Turkish position. US ambassador to the UN, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, slammed the Turkish airstrike against Makhmour and labeled the act a clear violation of international and humanitarian law since the camp was home to more than 10,000 refugees.34 In the Spring of 2019, during Operation Olive Branch, then-presidential candidate Joe Biden criticized then-President Donald Trump for withdrawing American troops from Syria to facilitate a Turkish military intervention against the PYD (PKK’s offshoot in Syria). Other countries also condemned Turkey’s strike on the refugee camp. For example, the Norwegian Foreign Ministry issued a condemnation and called upon Ankara to abide by international law.35

Perhaps the most interesting reaction to the airstrike came from the Iraqi government on June 6, 2021. In the past, Iraq had cooperated with Turkey to suppress the Kurdish independence project, but not anymore. The Iraqi forces spokesman, Yahia Rasoul, stressed the importance of Iraqi territorial integrity and asked Ankara to respect Iraqi sovereignty. He added that Iraq would act to stop TSK operations in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. Furthermore, Iraq requested Turkey to remove its troops from the country and share intelligence on the PKK.36

Despite international criticism, Operation Claw successfully pushed PKK fighters further to the south, to the territories governed by the KRG, creating conflict between the two Kurdish factions. This also reinforced Turkey’s rationale for creating a security zone within Iraq to keep Kurdish forces in check. The friction between the Kurdish actors peaked on June 5, 2021, when the PKK killed 5 Peshmerga soldiers of the KRG in an ambush in Duhok’s Metina region. While the KRG held the PKK responsible for the death of its soldiers, the PKK accused the KRG of collaborating with the TSK and of penetrating PKK-controlled areas where the Peshmerga had not entered for 25 years.

The Turkish Ministry of Defense seized the opportunity to stress that the PKK has no right to claim representation of the Kurdish nation. The Turkish Ministry of Defense even called for a closer partnership with the KRG against the PKK.37 Meanwhile, Turkey continued its strikes against the PKK.

The growing Turkish presence and assertiveness in northern Iraq also created tensions with Iran. The Iranian-backed group – Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces or Ḥashd al-Shaabi – felt threatened. The Shi’ite militias took the PKK fighters in the Sinjar area under its protection. They declared its intention to confront the TSK if Ankara expanded its activities in northern Iraq near the Sinjar mountains. Further, the Shi’ite militias tried to deter Turkey by carrying out a rocket attack on April 14, 2021, against a Turkish military base in Bashika, killing one Turkish soldier. The TSK chose not to retaliate.38 Thus, Turkey tacitly accepted limitations on its actions against the PKK to avoid confrontation with the Iranian-backed forces.

Syria

From the beginning of the civil war in Syria in 2011, Turkey sided with the Islamist-dominated Sunni rebels who sought the removal of the Assad regime. It actively supported the Free Syrian Army and the Turkomans, which were in the Jabal Turkman area. Moreover, Turkey turned a blind eye to the stream of jihadi volunteers transiting its territory to enlist in ISIS, which was hostile to the Kurdish PYD in Syria.

A result of the civil war was greater autonomy for concentrations of Kurds in Syria. Until its first ground offensive in 2016, Turkey refrained from sending the TSK into Syrian territory. However, in the aftermath of the failed coup attempt, direct military intervention against the burgeoning Kurdish entities in northern Syrian began. The invasion of Syrian territory also served Erdoğan’s domestic aims since it strengthened his alliance with the nationalist party (MHP) and simultaneously demonstrated his ability to control the TSK after the coup attempt. As a result, Turkey launched three limited military interventions in northern Syria in 2016, 2018, and 2019. It captured the Jarabulus, Afrin, and Ras Al-Ayn – Tel Al-Abyad cantons.

The Syrian regime fiercely denounced this Turkish military presence. On June 24, 2021, Syrian Deputy Foreign Minister Bashar Jafari accused Turkey of supplying arms to the jihadist Al-Nusra Front and turning a blind eye to the infiltration of jihadists into Syria. The Syrian official quoted Sedat Peker, a Turkish mafia boss, who fled to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) while accusing the Turkish government and military consulting company SADAT of smuggling arms to terror groups in Syria.39 Jafari also protested the systematic Turkification of northern Syria cantons and the stealing of Syrian oil, grain, and other natural resources.40

The Biden administration also opposed Turkey’s intervention in Syria and Iraq. In its 2021 Trafficking in Persons Report, the US criticized Turkey for supporting the Syrian Turkmen opposition faction, the Sultan Murad Division, which recruited children to its ranks.41 Moreover, the US State Department asked for an explanation regarding similar charges regarding Ankara’s actions in Libya.42 As a result, a NATO member was publicly accused of recruiting children as soldiers for the first time. Although Turkey rejected the report’s findings as baseless, the publication of such a report was a blow to Turkey’s legitimacy.

Another key issue resulting from the crisis in Syria was the passage of migrants and refugees from the Middle East via Turkey to Europe. Proximity to the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea made migration an attractive option for refugees in Turkey seeking to reach Europe. For years, the Turkish coast guard turned a blind eye to refugees who were heading to Greece. Indeed, asylum seekers from Somalia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Syria, and Bangladesh often reached the island of Lesbos in Greece, which is located only 12 kilometers from the Turkish mainland. However, after reaching an understanding with the EU in 2016, Turkey dramatically reduced the number of illegal migrants.

Despite the agreement, Europe adopted positions condemning Turkish behavior. For example, the European Parliament condemned Turkey on March 11, 2021, for illegally transferring weapons into Syria and occupying its northern region. Emphasizing the absence of a UN mandate to carry out a military operation, the EU asked Turkey to withdraw its troops from Syria.43 However, the resolution was not accompanied by sanctions and failed to deliver a tangible result.

The main reason for European inaction against Turkey is the EU’s dependency on the country in halting the refugee influx into Europe. EU officials criticize Ankara while simultaneously praising it for hosting Syrian refugees and emphasizing the EU’s commitment “to continue funding humanitarian assistance programs in refugee host countries,” such as Turkey. On June 23, 2021, the EU officially declared its intention to provide three billion euros in aid to Turkey for strengthening security along Turkey’s border with Syria.44 This economic aid package aims to gain time by encouraging Turkey to continue hosting the refugees.

AKP spokesperson Ömer Çelik underlined Turkey’s difficulties from refugees and signaled that it would request more aid.45 Thus, Turkey will probably continue exploiting the refugee card to soften EU criticism against its policies and secure economic assistance.

With financial support from the EU, Turkey completed construction in November 2020 of an 832 km.-long border fence with Syria. The completion of the fence significantly decreased illegal border passage. However, the discovery of a tunnel from Syria into Turkey on June 7, 2021, raised concerns regarding the efficacy of the fence.46

The Aegean Sea

The discovery of natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean magnified the conflict over the Aegean continental shelf, maritime sovereignty, exclusive economic zones, and maritime delimitation treaties. For Turkey, the East-Med pipeline project is a serious challenge to national security and its self-perceived role as an energy bridge between east and west. The pipeline aims to transfer Israeli and Cypriot natural gas to Europe via Greece, bypassing Turkey. Turkey dispatched its navy and a seismic ship to the contested maritime zones to demonstrate its opposition to this pipeline plan. Greece and Cyprus then asked for the assistance of the EU to contain Turkish aspirations.

The EU then signaled that it might impose sanctions against Ankara unless Turkey desists from its actions in the Eastern Mediterranean. Bearing in mind the deterioration of the Turkish economy, Ankara realized the severity of the problem and recalled its seismic ship, Oruç Reis. Greece and Turkey then resumed talks to find a solution to their disagreements. So far, these talks have failed to produce an agreement.47

Athens has tried to capitalize on anti-Turkish sentiment within the EU. For example, in a June 11, 2021, joint statement, seven Mediterranean members of the EU – Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, and Spain – called on Turkey to abstain from “unilateral actions in breach of international law.”48 Greek self-confidence reached its peak on June 14 during a Brussels summit between Greek Prime Minister Kiriakos Mitsotakis and President Erdoğan. The Greek premier told the press that he was not expecting any extraordinary events during the summer in the Aegean Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean. Despite this statement, Athens declared its intention to conduct a military drill in the Aegean Sea while arming demilitarized Greek islands. The Turkish side saw these acts as crossing a red line.

Consequently, on June 22, Ankara declared a new NAVTEX (a written warning to sailors and pilots not to pass through an area where a military drill occurs).49 Despite the NAVTEX declaration, the Turkish press did not specify the exact dates of the planned military exercise. The declaration was probably made for domestic public consumption.

Libya

To break the maritime contiguity between Greece and Cyprus, on November 27, 2019, the Turkish government signed a maritime delimitation agreement with Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA). The agreement dealt with the borders of their Economic Exclusive Zones (EEZs). The maritime corridor between Turkey and Libya provided Ankara a legal basis for its Blue Homeland doctrine, which expands its maritime borders at the expense of Greece and Cyprus.

Ankara intervened in the Libyan civil war in November 2019 to prevent the fall of the GNA government in Tripoli. This bold move was a de facto proxy war declaration against Russia, Egypt, and the UAE. Ankara helped shift the balance of power in favor of the GNA by its military intervention, arms shipments, and the deployment of Syrian mercenaries.

A cease-fire was reached on August 22, 2020, which required all foreign military personnel and mercenaries to leave Libyan territory, posing a problem for Turkey. However, Turkey could not reject the cease-fire terms due to Russian pressure. 50 Yet, Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar refused to label TSK personnel as foreign fighters. According to Akar, the TSK was “invited” into Libya by the “legitimate Libyan government.” Therefore, Turkish troops could not be compared with other foreign forces.51 Furthermore, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs statement on June 25, 2021, criticized the decisions of the Second Berlin Summit on Libya (June 23, 2021), which did not differentiate between mercenaries and the “legitimate trainers and consultants of the Turkish army.”52 Turkey then declared that it would not comply with the terms of the conference.53

But Turkey did not violate the cease-fire. On the contrary, Cairo managed to deter Ankara. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s June 2020 speech declaring the Libyan cities of Sirte and Jufra as Egypt’s red lines sent a message to Ankara. Sisi also asked Egyptian pilots to be ready to carry out any missions within and beyond his country’s borders.54 Egypt’s geographical proximity and its ability to send reinforcements to neighboring Libya give Cairo a considerable advantage over Ankara.

Given Turkey’s reluctance to withdraw its troops from Libya, Egypt delivered an important message to Ankara. On July 3, 2021, Sisi inaugurated a new Egyptian navy base in Gargoub with UAE Crown Prince Muhammed Bin Zayed in attendance, which was constructed for “securing shipping lines.” This can be seen as another message to Turkey’s so-called “ghost ships,” which were loaded with ammunition and heavy weaponry and traveled from Turkey’s Mersin port to Libya’s Misrata and Tripoli ports.

As talks continue over the future of Libya, Ankara seems to favor a divided country, which may suit Russia and Egypt as well.

Russia

Turkish interventions in various theatres such as Syria, Libya, and Nagorno Karabakh have imped Russia’s interests, leading to several diplomatic crises between Turkey and its historic nemesis Russia.

The two countries have been on opposite sides of the Syrian civil war. Frictions reached a peak on November 24, 2015, when a Turkish F-16 shot down a Russian SU-24 that violated Turkish air space while operating in Syria. Russia demanded an apology and imposed a tourism ban on Turkey (tourism is an important source of income for Turkey) and sanctions on Turkey’s construction and agriculture sectors.

President Erdoğan finally apologized on June 27, 2016, and mended fences with Putin.55 Erdoğan also visited St. Petersburg and expressed his gratitude to Putin for his diplomatic support during the failed coup attempt.56 This rapprochement opened the channel of a dialogue in which both sides could manage to control their rivalry. The assassination of Russia’s ambassador to Turkey, Andrei Karlov, by a Turkish policeman on December 19, 2016, was another diplomatic crisis that the two leaders quickly defused.

Ankara has also expanded its influence in the Syrian Idlib province at the expense of the Russia-backed Assad regime. Until now, Assad’s forces refrained from launching an all-out war on the city and settled for a war of attrition. Likewise, the Russian air force rarely attacks Turkish positions in Syria. A tense relationship also characterizes Syrian forces operating in proximity of Turkish-controlled areas in the north.

Tensions between the two states also devolve from Ankara’s diplomatic support of Ukraine on the Crimea question, including selling military equipment such as Turkish-made Bayraktar UAVs to Kyiv. Russia responded by reducing the frequency of passenger flights to Turkey from April to June, using the spread of COVID-19 in Turkey as an excuse to punish Ankara.57

Turkey also was an active actor in the latest Nagorno Karabakh war that lasted from September to October 2020 in the Caucasus between Armenia and Azerbaijan, a Shi’ite Muslim Turkic ethnic state. Ankara sold weapons, including UAVs, to Azerbaijan and dispatched Syrian mercenaries to the country. Russia, the ally of Christian Armenia, was primarily active in negotiating the deal that ended this war. Russia and Turkey sent peacekeepers, and thus – in theory – Turkey gained a land corridor to Azerbaijan via Armenian territory. However, the Russians were not happy about Turkey’s meddling in the former Soviet region. As a result, Russia chose once more to restrain Turkey with a tourism boycott.

Another area of latent conflict between Ankara and Moscow is the Black Sea. The Turkish position is colored by its desire to protect the rights of the Tatar Muslim community in Crimea, putting it at odds with Russia. But Turkey has acted cautiously regarding Russia. As a signatory of the Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Straits (1936), Ankara adopted the stance of the Black Sea riparian states58 rather than a NATO stance. Indeed, at Turkey’s initiative, the BLACKSEAFOR naval cooperation program (2001) – which seeks to eliminate differences among the Black Sea coastal states – was established in 2001, with Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Russia, and Georgia.

Thus, Turkey is refraining from angering Russia in the Black Sea area to maintain its sovereign rights stemming from the Montreux Convention. For example, Turkey did not cooperate fully with NATO in the Black Sea during the Russian-Georgia war in August 2008.

Moreover, in 2017 Turkish President Erdoğan decided to purchase the Russian S-400 mobile surface-to-air missile system. This system risks the NATO alliance and the F-35 fighter jet, America’s most expensive weapons platform.

The US responded by canceling the sale of F-35s to Turkey. Furthermore, on December 14, 2020, the US applied the “Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act” (CAATSA) to Turkey, an unprecedented move towards a NATO ally.

Nevertheless, Ankara continues to proclaim its loyalty to the NATO alliance. To prove its indispensability, Turkey even offered at the June 2021 NATO summit to take control of the Kabul international airport to defend it from Taliban forces after the American withdrawal. Moreover, a Turkish presence in Afghanistan could serve as another bridgehead to Central Asia, where most states are of Turkic ethnic origin. Yet, Central Asia is another Russian backyard.

Since Turkey has long considered NATO membership as a defense against Russia, it is unlikely that Ankara will ditch its insurance policy. Instead, given that NATO lacks a mechanism for removing a country, Turkey intends to get the maximum out of it.

In parallel, Turkey is mainly dependent upon gas supplies from Russia. After returning from Russia in September 2021, President Erdoğan’s announced a deal with Russia to construct two additional nuclear reactors, increasing Turkish energy dependency on Russia. Turkey also responded positively to China’s Belt and Road Initiative and has welcomed swap agreements between the two countries to facilitate trade.59

In short, Turkey is maneuvering by maintaining good relations with the US and being a good NATO member while maintaining close ties to NATO challengers. Whenever there is a disagreement with the US (for example, US arming of the Kurdish PYD), Turkey conducts rapprochement towards Russia. In contrast, whenever Turkey is challenged by Russia (as in Idlib and Libya), Ankara uses the NATO alliance as a shield against Moscow. This Turkish ambivalence has created discontent among NATO allies. Inevitably this has triggered an anti-Turkey discourse in Brussels, questioning the worthiness of Ankara’s membership in the NATO alliance.

Conclusion

In Iraq and Syria, the US and EU are seeking to undermine the legitimacy of Ankara’s actions. The EU has called for the removal of Turkish troops in Syria, and the US has protested Turkey’s bombing of the Makhmour refugee camp and classified Turkey as a country that recruits child soldiers.

However, given that the PKK is classified as a terrorist organization by the US and EU, and since Brussels needs Ankara’s cooperation to deal with the Syrian refugee problem, the reactions of Western countries to Turkey’s actions are likely to remain low key. Moreover, the West has tolerated Turkey’s support for Hamas in Gaza as well, despite the designation of Hamas as a terrorist group. However, if Turkey moves closer to Russia, Ankara may face more severe repercussions.

Russia is a world power, and Turkey is cautious when its actions could damage Russian interests. Moreover, it depends on Russia for energy, and Moscow does not hesitate to apply economic pressure on Ankara to moderate its behavior.

In contrast, Iraq and Syria are weak. While both states asked Turkey to withdraw from their territories, they refrained from militarily engaging the TSK. Iran, a stronger state, behaves differently. When Turkish troops challenged Iran-affiliated Hashd al-Shaabi, Iran drew “red lines” for Turkey, warning Ankara not to advance further into central Iraq and the Sinjar mountains. While all these players seek to contain Turkey, the Kurds (the KRG and the PKK) pay the highest price. Meanwhile, the Kurdish factions continue their intra-communal fights.

Turkey’s increasing interventionist stance has extended into the Eastern Mediterranean per its

Blue Homeland doctrine. Ankara has challenged the maritime sovereignty of Cyprus and Greece. Athens and Nicosia perceive the Turkish stance as a grave national security threat and have urged the EU to pressure Turkey. However, facing the threat of EU economic sanctions on its fragile economy, Ankara has been somewhat deterred. Therefore, it has moved to scale-back tensions in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean seas for the time being.

A similar situation has developed in Libya, a former Ottoman province. Following the announcement of a “red line” by Sisi, Turkish-backed GNA troops have refrained from advancing and later signed a cease-fire. Russia’s leverage on Turkey also was central to convincing Ankara to accept the terms of the cease-fire.

Turkey has not hesitated to use force to advance its objectives beyond its borders. However, it acts cautiously in the face of international criticism and the threat of sanctions. It seems that Ankara indeed can be induced to conduct a more restrained foreign policy.

Chapter Four: The Turkey-Israel Nexus

Introduction

Relations between Israel and Turkey flourished economically, diplomatically, and militarily during the 1990s. Israel has long maintained its desire to have strong ties with Turkey, an important regional player. Defense trade during the 1990s was worth hundreds of millions of dollars. According to the Israeli business daily Globes, trade rose to $2 billion in the first half of 2011, up from $1.59 billion in 2010. Turkey is Israel’s sixth-largest export destination.60 And in the first nine months of 2020, Turkey’s exports to Israel reached $3.2 billion, according to The Jerusalem Post.61 Major deals included a $700 million contract to modernize Turkey’s aging fleet of F-4 Phantoms in the late 1990s and a $688 million agreement to upgrade M-60 tanks from 2005 and 2010. Israel also supplied Turkey with various other sophisticated weapon systems, including selling 10 Heron drones in 2010 for $183 million.62

The Israeli Air Force was allowed to use Turkish air space to practice complex air operations, and there were collaborations in counterterrorism and intelligence. For Jerusalem, the closeness between the two governments was second only to US-Israel relations. Moreover, the common strategic agenda between Ankara and Jerusalem bolstered ties.

Erdoğan came to power in 2003 at the height of the Turkish-Israeli strategic partnership and heralded a new era of animosity between the two states. As explained in the first chapter, the deterioration in ties occurred as Erdoğan consolidated his power at home and redefined his country’s national interests. Turkey’s new foreign policy orientation distanced itself from the West and sought to enhance relations with Muslim countries, particularly along Turkey’s borders, creating inevitable tensions with Israel. Turkey’s growing anti-Israel stance also served the purpose of gaining a leadership role in the Muslim world.63 These foreign policy preferences were reinforced by domestic public opinion as Erdoğan realized that an anti-American and anti-Israeli/Jewish line was popular and brought votes.

This chapter reviews the main areas of tension between Israel and Turkey: Iran, Palestinians, and the East Mediterranean.

Iran

The most indicative Turkish demonstration of the Islamization of its foreign policy was the new approach to the Islamic Republic of Iran, which was once seen as anathema in Kemalist circles. Moreover, Iran became Israel’s archenemy following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, and it raised tensions by developing its nuclear program and its efforts to gain hegemony in the Middle East.

In August 2008, Turkey welcomed the president of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, for a formal visit. Additionally, the Turkish prime minister decided to congratulate Ahmadinejad immediately after his re-election in June 2009, despite protests that the vote was rigged and calls from the EU, which Turkey aspired to join, to investigate the election. Erdoğan visited Iran in October 2009, stating that “regarding settlement of regional issues, we share common views.”64 In Tehran, Erdoğan said that pursuing nuclear technology for peaceful purposes is the legitimate right of all world countries, including Iran.65 Turkey, which sat on the governing board of the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency, abstained in the Fall of 2009 from a vote to censure Iran for building a secret uranium enrichment facility near Qom.

In contrast to its NATO allies, Ankara even announced that it would not participate in any sanctions to prevent Iran from going nuclear. Turkey has consistently helped Iran circumvent economic sanctions imposed by the US. For example, in defiance of American attempts to impose harsher sanctions on Iran, particularly in refined oil products, Tehran and Ankara agreed in 2009 to build a crude oil refinery in northern Iran in a $2-billion joint venture project.66 The shift toward Iran was also motivated by energy-related considerations. Iran supplies Turkey with about a third of its energy needs. Turkey sought to preserve its relations with Iran and continued business with the Ayatollahs through its state-owned Halkbank. The Department of Justice announced on October 15, 2019, that it was charging the Turkish bank with fraud, money laundering, and sanctions offenses the bank allegedly made to evade US sanctions on Iran.67

In 2010, Turkey joined a Brazilian initiative to mediate between the West and Iran on the nuclear issue. This further aggravated Israel. The mistrust between Israel and Turkey deteriorated even further when the Turkish Intelligence Agency (MIT) was accused of handing over 10 Iranian citizens – who were allegedly working for the Israeli Mossad.68 Again in October 2021, the Turkish intelligence agency found itself in the news after it was reported that it arrested 15 so-called spies allegedly working for the Mossad.69

Despite Turkey and Iran’s shared interest in curtailing Kurdish nationalism and anti-Israeli attitudes, they were not full-fledged allies. Turkey’s encroachment into northern Syria and Iraq created tensions between the two. Azerbaijan was another bone of contention. There, Israel and Turkey were on the same side, arming Azerbaijan in the Second Nagorno Karabakh War in the Fall of 2020 against Iran’s ally Armenia. Yet, Turkey tried to mend fences with Iran using Israel. In August 2021, Ankara publicized Erdoğan’s call (August 2021) to the outgoing Iranian president Rouhani emphasizing the need to “deter Israel by giving it a lesson” and “the need to unify the Islamic world also for verbal and tangible actions.”70 That statement further damaged the bilateral relations between Israel and Turkey.

The Palestinian Issue

All Turkish governments displayed a soft spot on the Palestinian issue. Yet, this issue has gained greater resonance after the AKP came to power. Erdoğan’s Turkey escalated criticism of Israeli policies, with Erdoğan making occasional vitriolic statements peppered with antisemitic overtones.

Erdoğan’s decision to hold a dialogue with the terrorist group Hamas (the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood) in the aftermath of its bloody takeover of Gaza in June 2007 was an imminent sign of the tensions to come. Some Western states have been opposed to Hamas’ status as a legitimate interlocutor unless it accepts the existence of Israel, the agreements signed between Israel and the PLO, and renounces violence against the Jewish state.

Moreover, Turkey sided with Hamas during Operation Cast Lead in Gaza from December 2008 to January 2009. Even the pro-Western Arab states supported Israel’s struggle against Hamas during the conflict. Alongside Qatar, Erdoğan worked to bring about an end to the operation on favorable terms for Hamas. Erdoğan walked off the stage in Davos in 2009 after an angry exchange with the former Israeli President Shimon Peres in a discussion about the war.

Moreover, in September 2009, Jerusalem turned down a request from Turkey’s then-new Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu (2009-2014) to visit the Gaza Strip from Israel. He planned to meet Hamas officials before returning to the Jewish state.71 This decision was part of Israel’s policy of not meeting with international statesmen who meet Hamas officials on the same trip. Davutoğlu wanted to create the impression of mediation that was very important to Turkey’s leadership. Israel’s refusal to allow the visit infuriated the Turks, who decided to demonstrate their displeasure by canceling the participation of the Israeli Air Force in the international “Anatolian Eagle” exercise in October 2009.72 Ahead of his trip to Iran, the Turkish premier preposterously accused Israel’s Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman of threatening to attack the Gaza Strip with a nuclear weapon in an interview published in The Guardian on October 26, 2009.73

Israeli-Turkish relations hit new lows during 2009, which came at the same time as Turkey sought a leading role in the international arena by offering to mediate regional disputes such as between the US and Iran, Iraq and Syria, Israel and Syria, and Israel and the Palestinians.

Under Prime Minister Ehud Olmert (2006-2009), Israel disappointed the AKP government for not making enough concessions to Syria during the Turkish mediation effort in 2009. Around this time, Israel launched Operation Cast Lead, which was initiated to stop Hamas’ rocket fire against Israeli civilians.

Erdoğan also gave covert backing to the IHH Islamist organization and its Mavi Marmara flotilla in 2010 that intended to violate Israel’s lawful naval blockade on Gaza. When Israel stopped the flotilla by force, Erdoğan downgraded Turkey’s relations with Israel.

According to the Turkish press, in the aftermath of Operation Cast Lead and the flotilla, the 2010 Turkish National Security Policy Document, also known as the “Red Book,” refrained from defining Israel as a national security threat, but for the first time, it named Israel as “a destabilizing entity” for Turkish national security.74