By

The talks suggest that when common interests exist, Israel can engage beneficially and pragmatically even with enemies, resulting in de-escalation and mutual benefit.

Background

On October 14, Israeli and Lebanese working-level delegations met at UNIFIL headquarters in Naqura for one hour to begin talks on settling the disputed maritime boundary between the two countries. The talks were mediated by American diplomats David Schenker and John Desrocher (who is the US Ambassador to Algeria and who will continue to oversee the talks), as well as UN Special Coordinator for Lebanon Jan Kubis.[1] The two delegations sit in one room (with “social distancing” due to COVID), but there are no direct talks between the Lebanese and Israeli delegations. Opinions and positions are relayed between the delegations by the mediators.[2] The second phase of talks will be held on October 28.

History

In June 2000, after the Israeli withdrawal from South Lebanon, the United Nations demarcated or the disengagement line between Lebanon and Israel (the “Blue Line”). The line was based on the 1923 border between the British and French mandates, and was marked on the ground by the UN. There are thirteen points where the two sides disagree about the marking on the ground. The most notable of these is in the Har Dov/Shebaa Farms area, which before 1967 was the border between Lebanon and Syria and since that time has been the focal point of Hezbollah cross-border attacks.

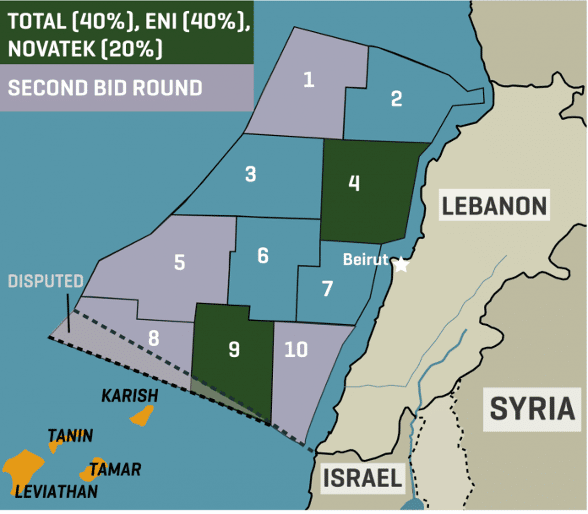

The maritime border between the two states was not marked, due to disagreement how it should be delineated. Israel plots the maritime border line by means of a 90-degree angle from the shore, while Lebanon draws it as a continuation of the demarcated land border. There is therefore a wedge-shaped, un-demarcated area in the sea between Naqura and the border of the Cyprus EEZ, comprising some 860 square km.

The United States has been attempting to mediate the border dispute for the past decade, through State Department officials Frederic Hof, Amos Hochstein and David Satterfield, in succession. Lebanon was distrustful of the US as a mediator, due to its close relationship with Israel and its stance on Hezbollah. It also demanded that the land disputes be addressed as well. Satterfield (then Acting Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs and now US Ambassador to Turkey) seemed to be making significant progress last year, and it seemed the sides were close to agreement. However, talks planned for Naqura last summer were scuttled by the Lebanese side, apparently due to pressure by Hezbollah.

The disputed area gained significant importance with the discoveries, beginning in 2009, of sizeable natural gas deposits in the Eastern Mediterranean, by Israel, Egypt and Cyprus. Lebanon (like Turkey) has so far not shared in the gas bonanza. Israel discovered natural gas near the Lebanese maritime border, notably in its Karish and Tamar fields. An area adjacent to Karish, now known as Block 72, was destined for exploration by Noble Energy and Delek. However, this block was not developed for a decade. The companies claim the government prevented exploration for diplomatic reasons, and their license was revoked in April by the Israeli Energy Ministry, which then reopened bidding for the block in June.

Block 72 is adjacent to the disputed area, and abuts Block 9 of the Lebanese gas exploration plans, the rights to which were licensed in 2018 to Total, Eni and Novatek. It is assumed that any gas deposit in the area would stretch under both sides of the disputed boundary. The three companies have so far been unable to explore and exploit Block 9, due to the dispute over the maritime boundary. The deterrent effect of the dispute was also widely held responsible for the lackluster response to Lebanon’s debut international gas licensing round in 2017.[3] The Israeli decision this year to open bidding on Block 72 caused consternation and strong reaction in Lebanon. Lebanon sees gas exploration, especially in Block 9 and the adjacent Blocks 8 and 10 (which have not yet been licensed), which are near proven Israeli gas deposits, as one of the possible routes out of its current economic crisis. It is important to note, however, that Lebanese survey results in other areas have so far proved disappointing, and that in any case the global and regional markets are currently depressed, so that development of any discoveries may well not be profitable in the near term.

Analysis

The US has been interested in mediating a solution of the maritime boundary issue for a decade. Some observers see the current timing as an attempt by the Administration to achieve another dramatic diplomatic success before the upcoming Presidential elections. Others afford significance to the fact that US energy giant Chevron bought out Noble Energy this summer (it placed a bid on Block 72 last month). The involvement of the interests of a big and politically influential American company could be an impetus behind renewed US efforts, as well as a consideration for the diplomatically beleaguered Lebanese regime. Moreover, US policy has been driven since the last outbreak of war in 2006 by the vision of generating a win-win situation which would shore up stability and serve as a disincentive for Hizbullah’s igniting a major crisis.

Israel has long shown interest in solving the maritime boundary issue. Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz, who handled the pre-negotiations on the Israeli side, has reportedly been authorized to signal Lebanon that Israel is prepared to split the contested territory in a 58:42 ratio, in Beirut’s favor. Solution of the dispute would enable exploitation of the promising Israeli gas parcels abutting the disputed area. On a larger level, it would display Israeli pragmatism and moderation; serve the broader interest of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum nations (including France, whose leverage in the region has been growing) as they face Erdogan’s ambitions; and amplify the narrative of diplomatic success vis-à-vis the Arab world, a key component of Prime Minister Netanyahu’s political messaging.

The greatest change is in the Lebanese position. As noted, Hezbollah had a de facto veto over the negotiations (handled by Parliament Speaker Nabih Beri – head of the Shia Amal organization and a key Hezbollah ally), due to predominance in recent governments of the party and its allies, including Beri and President Michel Aoun. This was in keeping with its desire to maintain the “Resistance narrative”, reject negotiations which would result in compromise on Lebanon’s border claims, and thus buttress its position as the guardian of Lebanon’s sovereignty. However the economic crisis in Lebanon, has led to the collapse of the currency and widespread suffering, pointed out the failure of the current government system based on sectarian “division of spoils” and rent-seeking, and led to large-scale public demonstrations.

This, added to strong popular and international criticism of the organization following the Beirut port disaster, seems to have caused the organization to seek to avoid being seen as obstructing efforts to improve the state’s failing economy. It may especially wish to avoid being seen – especially by Russia and Europe, whose companies hold the Block 9 license – as the only party hampering a solution. The Lebanese government’s wish not to offend Washington at this sensitive juncture, as well as Israel’s opening of bidding on Block 72, may have served as accelerants to Lebanon’s change of position as well.

What Can We Expect, and Not Expect?

There is a trilateral effort to manage expectations from the talks:

- Lebanese official sources have stressed that the talks will be indirect, and that the Lebanese delegation’s mission is to “conduct technical negotiations on the demarcation of the maritime border first and later the land border,” and will not lead to peace negotiations. Hezbollah for its part stressed (Oct. 8) that the talks did not signify “reconciliation” or “normalization” with Israel. It stated that “defining the coordinates of national sovereignty is the responsibility of the Lebanese state.” After the initial talks, the head of the Lebanese delegation, Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations Brig. Gen. Bassam Yassin said: “Our aim is very strict and limited and therefore hopefully achievable … we are looking to achieve a pace of negotiations that would allow us to conclude this dossier within reasonable time.

- Schenker noted on Oct. 5 that “these discussions are solely focused on establishing a mutually agreed maritime boundary so that both sides can take advantage of potential national natural resources.”

- Israeli officials have downplayed expectations for a wider diplomatic opening with Lebanon. Steinitz stated on Oct. 12 that “the expectations from the negotiations need to be realistic. We are not discussing negotiations on peace or normalization, but rather an attempt to solve a technical-economic disagreement which has for ten years prevented the development of natural resources at sea for the benefit of the region’s peoples.”

Nothing in the above analysis, of course, guarantees success of the negotiations themselves. Lebanon’s negotiators and their masters may demand a greater share of the disputed area than seems to currently be on offer, to avoid being accused of selling out national sovereignty. Lebanon currently lacks a government, and the public mood will withhold legitimacy from any new government to be formed in the coming days and weeks. This is not an ideal situation to carry out politically sensitive negotiations. Perhaps this, as well as de-politicizing the issue, are the reasons why Aoun is placing the negotiations under the ostensible control of the military.

In addition, Hezbollah may decide to turn against the negotiations (Iran’s position and role is unclear), as it has done before, or at least, make the conclusion of a maritime EEZ agreement contingent upon an Israeli acceptance of their extravagant land claims. And Israeli officials, although quite careful so far, may not be able to forswear crowing about the political aspects of the talks, linking them with the successes in the Gulf, and thus cause “cold feet” and posturing on the Lebanese side.

The maritime boundary talks, despite breathless press commentary and the proximity of the announcement to the diplomatic breakthroughs between Israel and UAE and Bahrain, do not signify another step towards formalization of Israel’s relations with its Arab neighbors. (Though some Israeli observers view them as a de facto recognition of Israel, Lebanese representatives have in fact negotiated with Israelis over the years).

However, they are quite significant both for their possible effect on the regional gas market (and as a second order effect, on the wider geostrategic positions it has engendered), but also because they indicate the possibility of normalization, in its more precise meaning. This would be a mutual interest in undeclared but effective non-belligerence, at least at sea.

The talks could be an indication that Israel can engage beneficially and pragmatically with countries which are otherwise viewed as hostile and even classified as enemies, leading to mutual benefit and de-escalation. As Arab states examine their future policies towards Israel in the wake of the “Abraham Accords,” this is a message which can resonate across the entire region.

[1] Israel had opposed UN auspices for the talks, so that in the end, Kubis will host the sessions at Lebanon’s insistence, but his notes will not be filed at the UN.

[2] This is a modality already used in monthly tripartite talks between the two sides and UNIFIL on ongoing border and security issues, where reportedly the two sides at this point address each other directly at this stage.

[3] “Israel/Lebanon politics: Quick View – Israel and Lebanon agree to maritime talks”, EIU ViewsWire, October 1, 2020.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.