The doctrine behind Israel’s UN warning to Lebanese civilians with a warhead for a tenant

By Amir Oren

In the Wild West of Hollywood drama, a Good Guy confronts a Bad Guy in a deserted Main Street – some frightened faces can be seen behind nearby windows – and the faster gun wins. Not the faster draw, because the noble Sheriff or innocent bystander who can’t stand injustice will not start the duel. He will have to respond and yet be quicker. Happy end.

In the much wilder Middle East, it is not so simple. Legitimacy is important, both domestically and internationally, but seeking it should not be suicidal. The most eloquent eulogy is no match for survival, even when rules – whose? – are bent in its pursuit.

This is the underpinning of Israel’s decades-old doctrine of pre-emption. When faced with imminent attack, it fires the first shot at the would-be aggressor, rather than be forced into a defense against invasion of its territory or a massive bombing of its population centers. Leaving the initiative to the other side, when it can decide whether to launch an offensive or wait out the stamina of an Israeli economy dependent on hundreds of thousands of civilians mobilized for open-ended reserve duty, is untenable.

Therein lies the reason for Israel’s breaking the siege around in in June 1967, with the cost of a French embargo, but also its understanding in October 1973 that with an outer belt of territories it occupied in that Six-Day War and the priority of getting Anerican arms and political backing, it can withstand an Egyptian-Syrian attack and still win a short war. Having over-rated itself and under-rated its enemies, it turned out to have been wrong. But ever since the Yom Kippur War, no Arab country has given Israel to pre-empt. Terrorist organizations frequently did, but not governments of UN member states.

Pre-emption is time critical. If the targets about to be hit in one’s territory are cities, casualties can be counted in the hundreds and thousands. If air-bases and other military assets are targeted, Israel could be effectively disarmed by the first strike, with the stark choice, especially regarding the Air Force, being use it or lose it.

These ideas developed and sometimes derived from the strategic debate in the 1950’s and 1960’s between scholars, officers and politicians in the West regarding the nuclear showdown between the United States and the Soviet Union. Terms like “counter-value” – civilian targets – and “counter-force”, “launch on warning”, “no first use”, along with books and movies such as Fail-safe and Dr. Strangelove, which illustrated the dangers inherent in deterrence when pre-planned steps get out of control by central authorities.

Throughout the 45 years of Cold War, and despite the bitter surprises of Pearl Harbour, the North Korean invasion of the South and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the Superpowers refrained from pre-emption and preventive war, the latter meant to cut short an adversary’s effort to build its military and choose the time for an offensive, in Third Reich fashion.

Israel had contingency plans for preventive wars if it sees overwhelming dangers across its borders, whether in Egypt or Jordan (an Iraqi expeditionary force crossing the Jordan River and positioning tanks in the West Bank, a short drive from Jerusalem and Tel Aviv). But the only overt operations it undertook before unacceptable threats materialized were against nuclear reactors, Iraq’s in 1981 and Syria’s in 2007. Conventional build-ups were not deemed worthy of the costs involved in initiating a present war for fear of an uncertain future one, after a “War of Choice” rather than one of absolute necessity on worse terms, as the Begin government tried to explain the invasion of Lebanon in 1982, hiding its real motives, failed to convince a skeptical public.

Enter Nasrallah and Netanyahu, two of the longest-serving leaders in the region, the Hezbollah chief going back to 1992 and the Israeli Prime Minister first taking office in 1996, with a 10-year hiatus. Hezbollah has close to 200,000 missiles and rockets aimed at Israel, along with infantry units training to raid and invade. Israel has an advanced air defense system, but with so many warheads hurled at it, saturation – and the cost of thousands of expensive anti-missile missiles – could overwhelm the defenses. Israel must prioritize. It will opt for a short, lethal and effective ground thrust into South Lebanon in order to over-run closer-range rockets and concentrate its air defense batteries around Fighter bases and infrastructure facilities, the latter also probably subject to Cyber attacks.

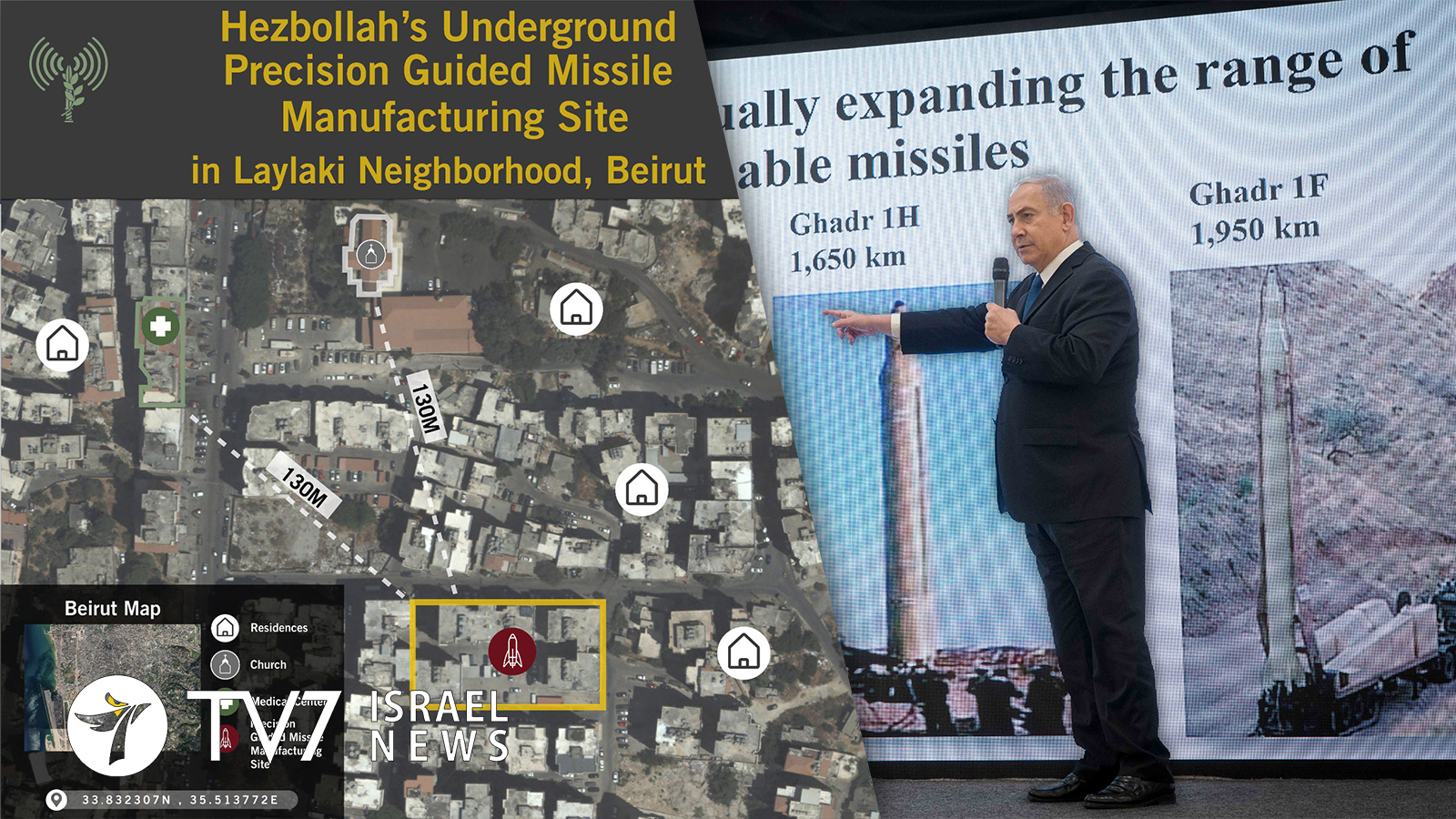

But out of the plethora of projectiles, only a few dozen – at current count, which could grow by import or upgrade – really bother Israel. These are the precision guided munitions, with pinpoint accuracy. Their posession could give Nasrallah or his Iranian handlers the idea, or illusion, that they could gain something by springing an attack. Israel thus wants to deny Hezbollah these assets both for maintaining deterrence and for improving its chances in conflict should deterrence fail.

But deterrence in the Israeli-Lebanese context is mutual. Israel credits Nasrallah with genuinely aiming to retaliate for every attack inside Lebanon’s territory. This equation holds between wars, not during them. With that in mind, Netanyahu’s revelation regarding the proximity of a missile retrofit facility recklessly close to a gas plant and residential neighborhood in Beirut had three obvious intentions.

Firstly, as Lebanon is slow to recover from the devestating August 4 explosion, to discredit Hezbollah, challenge its narrative as the country’s shield and loosen its grip on power. This may resonate with the general public and be helped by French anger at Hezbollah disrupting the establishment of a clean and accountable government, but will do little to dislodge Nasrallah from his perch as a power broker.

Secondly, to encourage civilians in Beirut, Baalbek and Baabda to resist efforts, by pressure or incentive, to literally hide bombs in their basements. Hezbollah has been placing missiles in private homes, setting aside for it existing rooms or building additional ones – boarders across borders. Their landlords are the weapons’ hosts in peacetime and their hostages in wartime, because Israel is not going to spare them. Perhaps some of them would be concerned with their families well being more than they fear Hezbollah or need the rockets’ rent. It is even conceivable that those who cannot openly break with Hezbollah will find ways of helping Israeli intelligence in return for their dwellings being passed over when war comes to their neighbors who collaborate with Nasrallah’s organization.

Finally, when the F-16’s come calling at these Hezbollah-rented Airbnb’s, courtesy Bibi’s Air (or whoever heads the Jerusalem government by then), it is better for both Israelis and Lebanese that civilians evecuate the places known to be on the Fighter’s crosshairs. There is no moral justification for human – and urban – shields, be it for rockets or tunnel digging, and if Israel is willing to risk holding off on pre-emption, though it will not commit to abandon this option altogether, the onus is on Hezbollah to put its weapons out of town and on civilians, reluctant or willing hosts, to get out of harm’s way.