The Diplomacy of Drilling

By Amir Oren

Negotiations between enemies are hard enough because of the conflicting interests of nations (or organizations and movements, be they FLN in Algeria, the PLO or Hezbollah), institutions taking part in decision making (such as Foreign and Defense Ministries) and individual participants – Presidents, Prime Ministers, Generals. This was the basis for Graham Allison’s seminal analysis of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, “Essence of Decision”. There was a concept of an American interest, but also important inputs by President Kennedy and down the line the US Navy and its chief, Admiral Anderson.

That crisis had three parties – Washington, Moscow and to a lesser extent Havana – and no outside mediator, though the American and Soviet governments also used unofficial channels. But when parties are not on talking terms, mediation is crucial. A series of American and European go-betweens failed to bring about Israeli-Egyptian talks in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, until Henry Kissinger came along, helped by the aura of his diplomatic breakthroughs in China and Vietnam. Later, when indirect contacts between Sadat and Rabin – and then Begin – stalled, Morocco’s King Hassan played a key role in bridging the gap.

A lot has to do with picking the right man (or woman) for the mission. Care should be taken, lest the mediator be perceived even before he sets out to be favoring one of the parties. This is why Kissinger balked for the entire first term of the Nixon Administration at openly dealing with the Middle East, fearing the Arabs would hold his Jewishness against him. A decade later, it did not help Philip Habib, a seasoned diplomat mediating between Israel, Syria and Lebanon, that he was of Lebanese extraction (a fact probably making him even more suspect in Damascus than in Jerusalem).

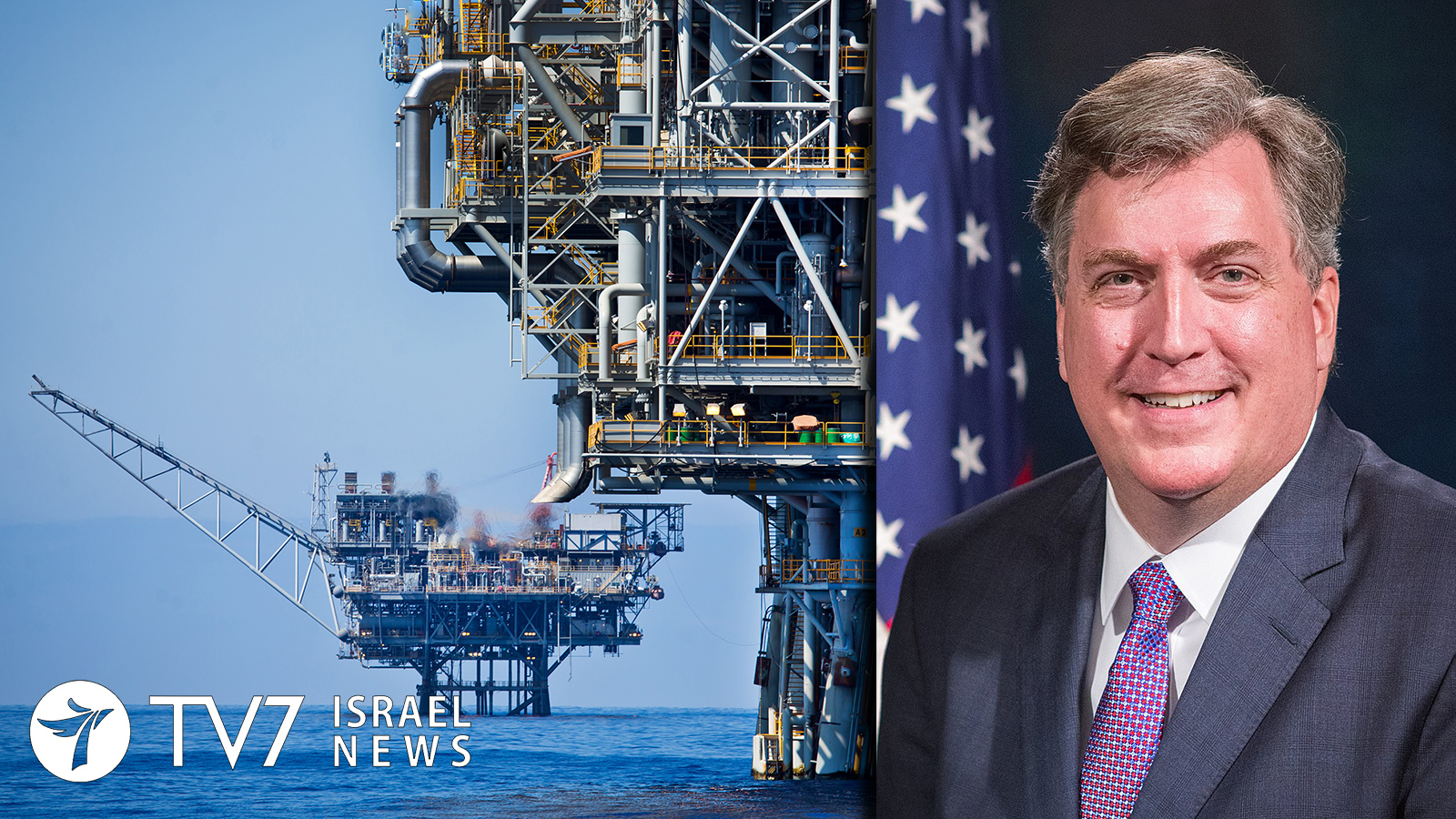

The US State Department has for once, seemingly, learned this lesson well. As the UN-hosted Nakura talks between Lebanon and Israel on the demarcation of their maritime boundary start, it has announced the appointment of Ambassador John P. Desrocher, its envoy to Algeria, as mediator on its behalf.

As Comedian Larry David would have advised, curb your enthusiasm. These are only talks about talks. The discussion would first focus on the modalities for dealing with the issues at hand. This will help the Beirut government bypass the counterforces resisting any official contact with Israel. Conversely, if the Lebanese Army is standing in for Beirut, the problem of Hezbollah’s participation in the cabinet, anathema for Israel, can be put off for another day.

As for substance, there are good prospects for success, as both countries want to settle their dispute over a certain block of the Mediterranean under which probably lie huge gas reserves. They will quibble over percentages of overlapping demands for Exclusive Economic Zones, but in the final analysis Lebanon is in a better bargaining position, as it is in Israel’s high strategic interest for Lebanon to become prosperous and stand to lose a lot from a devestating war instigated by Iran via Hezbollah. Israel would gain in diplomacy what small concession it will have lost in drilling.

But this is not pre-ordained, and the identity of the mediator can have some impact, as it did when Ralph Bunche brought about the 1949 Rhodes Arab-Israeli Armistice Agreements and Canadian Foreign Minister Lester Pearson pushed through the idea of a UN force in Sinai to deter Egyptian aggression and save Israel’s face.

America’s man at Nakura, Desrocher, seems to have the right credentials, neither too little nor too many. He is well versed in the two cultures important to the Lebanese elite – Arabic and French. Having served in Iraq, he understands the region and Iran’s efforts to undermine stability. His staff work at State’s Near East Affairs bureau has given him a broad view of the Levant and a feel for the Washington machinery.

Desrocher’s strong suit is said to be international trade – key to these talks where all eyes are on the bottom line. As an Economic Officer at the Jerusalem Consulate General, 1997-2000, he took part in the Oslo basket of Palestinian-Israeli economic talks, so he knows something about Israel and its perception of the interplay between diplomacy and dollars, yet he would not be marked as pro-Israel just because he served there – the Jerusalem Consulate being considered a de facto embassy to the Palestinian Authority and reporting to headquarters in D.C. outside of Tel Aviv embassy chain of command.

Another plus by omission is that Desrocher has never served in Lebanon. He has no prior relationship, friendly or otherwise, with any group or power-broker there. As he begins his mission, no-one can claim that this professional comes with a bias.

- Of course, it will ultimately be up to the parties, with their long history of false starts (the May 1983 peace agreement imposed on Lebanon by Israel and the US, quickly aborted by overwhelming Syrian pressure; a late 1990’s forum convened at the same Nakura venue following the “Grapes of Wrath” IDF campaign in South Lebanon). But is a positive indicator when the power both sides look up too has detailed for this task a diplomat who seems to come equipped with the right toolbox.