– By Dr. Dima Course, an expert on the politics and security of the post-Soviet states.

A network of personalities and organizations in Russia can be said to be directly or indirectly promoting the interests of Iran in Russia in various fields. However, Russia and Iran are not allies and treat each other with considerable suspicion. This is a constraint for the Iranian lobbying effort.

Iranian Interests in Russia

The following key policy objectives can summarize Iranian interests in Russia. First, Iran seeks Russian support for its demands in the Vienna negotiations to return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). In addition, Tehran sees Moscow as an ally that can serve to reduce the West’s influence in the Middle East.

Tehran also seeks the promotion of its economic interests, which include foreign investment, trade, the removal of sanctions; the acquisition of advanced Russian weaponry; cooperation in propping up the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, and in reducing the influence of Turkey in the Southern Caucasus and Central Asia.

Iran is also interested in improving its image in Russia. Specifically, Tehran promotes a narrative that presents the Iranian revolution to the Russians in terms of a “distinctive conservative culture bravely fighting against destructive globalism guided by the West.” In addition, Iran attempts to use, and even enhance, anti-Western, and specifically anti-American, sentiments in Russia to bring the countries closer.

Acknowledging Russians’ traditional wary perception of Islam, Iranians diligently present themselves as bearers of a moderate version – even standing together with others in the region and the world against “terrorists” such as ISIS. In addition, their propaganda presents Iran as a critical partner and even ally of Russia, which hardly corresponds with reality.

The areas and methods of Iranian activities in Russia can be divided into three main categories, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

| Audience \ Target | Methods |

| Officials + Public Opinion | Informal ties with officials + influencing media, academia, social networks, etc. |

| Muslims of Russia | Promoting the theological agenda of Iran |

| Local elites \ media \ public opinion | Funding of joint programs, informal ties with relevant persons\organizations |

First, a key characteristic of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s regime, which is crucial for understanding the Iranian modus operandi, should be clarified. Many studies1 present the same phenomenon, albeit using different language and images. They describe Putin’s regime like a double-bottomed suitcase. There are two completely separated dimensions: the formal one, in which the actions of officials and citizens, in general, are governed by laws and regulations, as they should be; and the second, the more significant dimension, where domestic actors receive de-facto autonomy according to their status of informal relations with the higher.

What in the West is called “corruption” in Russia is perceived as the state’s normal distribution of resources. “Resources” do not necessarily mean funding from the federal budget, but also the autonomy to informally receive benefits from an external actor – Iran, in our case – and not be punished for that.

For example, a state news agency’s managers benefit from the Iranian embassy for favorable coverage. Formally, it is a severe violation of the law. However, in reality, if the funding country is defined as friendly and the coverage does not harm Russia’s image, and the receiver of benefits is considered loyal enough to the regime, the act will be regarded as proper. Probably no punitive measures would be taken. Iranians understand this system well and are taking full advantage of it.

Political and Bureaucratic Elites

Iranian lobbying efforts at the highest levels of the Russian government are mostly hidden from the public eye. Fully funded trips to Iran by Russian parliamentarians or high-ranking government representatives can be mentioned in this context but do not necessarily prove anything beyond their official duties.

For example, take Viktor Ivanov, the head of Russia’s Federal Drug Control Service (FSKN) from 2008 to 2016. Ivanov held sway in the Russian government since he had worked under Putin in the early 90s in the St. Petersburg mayor’s office. Ivanov was close enough to Putin to move up the hierarchical ladder quickly. Putin won the presidential elections in 2000, and Ivanov became the Deputy Chief of Staff of his administration.

In 2008, when Ivanov headed the FSKN, his main task was to block drug trafficking from Afghanistan. One of the smuggling routes passed through Iran and then through the Caspian Sea. At first, Ivanov publicly mentioned Iran as one of the states responsible for drug trafficking along with all the Central Asian states and Turkey.2

However, as the cooperation with his Iranian colleagues grew, Ivanov’s rhetoric significantly changed, and Iranians turned into significant partners fighting a common enemy.3

However, due to Ivanov’s quarrels with related governmental agencies such as the Federal Security Service FSB, Interior Ministry, and others over control, in 2016, Putin dismantled the FSKN. As a result, Ivanov fell into disgrace for two years, after which he returned to civil service with a significant reduction of status. As a result, Iran probably lost one of its most highly ranked advocates in Moscow.

Does Anti-US mean Pro-Iran?

It is essential to distinguish between two types of politicians in Russia that are sympathetic to Tehran. First, many support Iran, not because they identify with its agenda and interests but rather because their visceral hostility to the US makes Iran a convenient ally. For this group, a pro-Iranian theme is a way of expressing their anti-US views.

An example of such a figure is Sergei Mironov, the leader of the Spravedlivaya Rossiya (A Just Russia) party. The party is a satellite of Putin’s United Russia party but is to the left of it on economic issues and to the right on nationalism and foreign policy.

Between 2001 to 2011, Mironov served as chairman of Russia’s Federation Council – the upper house of parliament. This is the state’s third-highest position and from which Mironov consistently defended Iran and accused the West of fomenting conflict with Tehran. He worked closely with the Iranians, visited Tehran, and received Iranian delegations in Moscow.

Mironov continues to be in close contact with Iran today despite a significant reduction in his political clout in Russia.4 Mironov’s positions and personality show that he shares some conservative and anti-liberal values with his Iranian counterparts. His support of Tehran depends on Russian – Western tensions rather than a pro-Iranian predisposition.

Another group, more relevant for this study, is distinguished by a more profound and more principled sympathy for the Shi’ite regime. Naturally, they are more willing to cooperate with the Iranians and are even ready to risk their status in Russia to defend Iranian positions.

The Case of Rajab Safarov

Prominent among those who match the classic description of a lobbyist for Iran is Rajab Safarov. A respectable scholar born in Tajikistan, he made an impressive career in Russia. Already in the early 90s, he was frequently cited in international relations. By the end of the decade, he became a high-ranking researcher in the diplomatic academy of the foreign ministry. Even then, he was already an active lobbyist for Iran.

In the 2000s, Safarov used his reputation and access to the State Duma and the media to promote the Iranian agenda. He whitewashed the Iranian nuclear program and denigrated Israel. Following the Second Lebanese War in 2006, he diligently promoted Iranian views on the conflict in Russia’s mass media. The scope of his influence has undergone major changes over the past 20 years.

Safarov simultaneously managed a private research institute for the study of Iran that included two serious journals – one dedicated to the scholarly study of Iran and another designed for the business community in Russia, presenting business opportunities in Iran. However, by 2016 all these projects were frozen. Therefore, in 2017, Safarov resigned as Advisor to the Deputy Chairman of the State Duma of the Russian Federation, a position he had held since 2004.

While in this position, he advised the Russian – Iranian inter-parliamentary working group. In addition, he oversaw a news website, Iran.ru, which has become quite popular. This website serves as the mouthpiece of Iranian propaganda in Russia. Its content consists mainly of glorifying the Shi’ite regime, its supposed successes, demonizing Israel, and condemning Western values. In addition, Iranian-Russian relations are presented on Iran.ru enthusiastically and as a strategic partnership.

The Izborsk Club

In 2012, a new think tank called the Izborsk Club was established to employ Russia’s anti-liberal, anti-Western, and ultra-patriotic intellectuals. However, the core views of the Izborsk Club experts differ significantly. Some of them come from the Marxist left – nostalgic for the USSR. Others express reverence for Russia’s monarchist past.

The ideological differences among the experts did not matter much and most of them were Iran backers. Most of the staff, and particularly its leaders, were part of the radical fringe who were derided to the margins in the 90s and early 2000s.

However, the gradual turn of Putin’s regime towards neo-imperial ideas and confrontation with the West turned them into leading commentators in state media and recognized experts of the Duma committees, the government, and the presidency.

Chairman of the Izborsk Club, Alexandr Prokhanov, is a veteran journalist and a devoted supporter of the “Palestinian struggle” against Israel and a fan of Hamas. His writings are pro-Iranian and anti-American\Israeli.

A few ideas published by the experts of Izborsk in the last few years deserve attention. These include the inclusion of Iran in the Collective Security Treaty Organization led by Russia and a proposal for Russian leaders to openly support Iran, even if it leads to a confrontation with the West. Furthermore, they call for Iran to become a strategic ally and allow Russia to establish naval bases on the Indian Ocean. Finally, they have also proposed sharing a sphere of influence with Iran and Armenia to weaken Turkey’s and NATO’s influence in the South Caucasus.

In addition, experts at the think tank promote the concept of spiritual and civilizational closeness between Russia and Iran. For example, influential ideologue Aleksandr Dugin visited the country and was especially impressed by the holy city of Qom. Dugin has written about Iran and even completed a monograph in 2014 arguing that despite all their differences, there is a potential for a “Russian Orthodox – Shi’ite alliance.” According to Dugin, Shi’ite and Russian Orthodox cultures share the traditions of martyrdom and self-sacrifice for higher ideals.

Despite challenges, this alliance contributes to the view that Russia’s mission is facing the “godless” West. Katechon (Retaining in Greek) has become a key concept in Russian political philosophy presenting Russia as a “holy state” that by its very existence may prevent the end of the world by the appearance of the Antichrist. Russia inherited this concept from Byzantium, along with Orthodox Christianity. It appears esoteric, but it is deeply rooted in Russian political culture.

In recent interviews and publications, Dugin emphasized that Russian, Syrian, and Iranian fighters in Syria are on the same side of the barricades, while on the other side are those associated with the devil. This idea has the potential to gain popularity since Russian – Western tensions have deepened.

The Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (RISS)

The spiritual concepts of Izborsk are echoed in the publications and conferences of RISS – a state-owned think-tank directly serving the Administrative Directorate of the President of the Russian Federation. It had been a think-tank of the KGB and after the collapse of the USSR – of SVR, Russia’s CIA. In 2009, it started serving the presidency. From 2009 to 2017, the institute was headed by lieutenant general (ret.) of SVR, Leonid Reshetnikov, who holds views similar to Dugin and his Izborsk colleagues.

Under Reshetnikov, RISS welcomed anti-Western and anti-liberal views, including pro-Iranian narratives. Dugin was an honorable guest at a few RISS conferences in 2016, including a roundtable with Iranians where he presented his concept of the “Russian Orthodox – Shi’ite alliance.”

In addition, the institute’s researchers published papers and books defending the legitimacy of the Iranian nuclear program and blaming the US and Israel for drawing attention to the issue. They claimed that no one could demand that Iran freeze its nuclear program without a similar demand of Israel.

However, in 2017, Reshetnikov was replaced by the former prime minister and head of SVR (2007-2016), Mikhail Fradkov. Under Fradkov, RISS started propagating more moderate views. Some of the most extreme researchers also left. Since 2017 the institute’s analysis on Iran has become more reasonable and less ideological.

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC)

In Putin’s regime, people and organizations can accumulate political or economic power without an official position and in exchange for loyalty. The ROC worked closely with Izborsk Club and RISS, at least until 2017. ROC’s priests and civil employees have written papers for Izborsk.

Further, ROC manages its international relations with the quiet approval of the Kremlin. Considering the significant differences with Shi’ite Islam, their diplomacy towards Iran is quite intensive. Reciprocal visits between clergy take place as a part of interreligious dialogue. Moreover, the head of ROC, Patriarch Kirill, maintains relations with the Iranian leadership through the Iranian ambassador in Moscow. In 2015, Kirill’s appeal was enough for Iran to release a Protestant pastor sentenced to seven years in prison for missionary activity.

The Russian Academy of Science

Iran uses its embassy and consulates in Russia to form an academic connection between the countries and promote its cultural and political agenda. This section presents four examples of such cooperation with leading universities in Moscow. In the following section, the activities of Iranians in universities outside Moscow are discussed.

The Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Science in Moscow (IVRAN), probably one of the country’s largest and the most influential academic institutes, has a section dedicated to Iran. So naturally, the Iranian embassy focuses on the institute, and it seems the effort is quite fruitful. In 2020, the Head of IVRAN, Dr. Alikber Alikberov, met with Iranian ambassador Kazem Jalali and stressed that his institute “has no such relations with any other embassy, except the embassy of Iran.”5

Another such research center is the International Center for Russian – Iranian Studies RSUH at the Russian State University for the Humanities in Moscow. The center was established in 1999 with the participation of the Iranian embassy, the Iranian Cultural Center in Moscow, and the Academy of Sciences of Iran. The center maintains deep cooperation with Iranian universities, sending trainees to universities in Tehran, Mashhad, and Isfahan. In turn, it hosts students and lecturers from Iran.6

The department of Iran studies at the prestigious Moscow State University (MSU) has been active since 1956 and in recent years has cooperated with the Iranian Cultural Center in Moscow. In contrast, the Moscow School of Economics, known in Russia as VYSHKA, had no research unit dedicated to Iran until 2019, when the embassy of Iran assisted them in establishing it.

The Use of the Muslim Card

Historically, Shi’ite Muslims have always been a tiny minority of no more than 5% among the Russian Muslim minority. Their historical residence is in Dagestan, bordering Azerbaijan.

Iran has promoted Tashayu’ – conversion to Shi’ite Islam – in Russia and Central Asian states, mainly through the activities of the Ahli Beit movement. The movement succeeded in establishing branches across Russia, promoting Iranian interests, and challenging the majority Sunni tradition of Russia’s Muslims. 7

Ahli Beit and its affiliates (that do not always make their affiliation public) continue functioning today. However, it seems that since 2016 at the latest, this activity began to face serious obstacles.

Its website, Ahlibeyt.ru, has not been updated since 2015. In 2016, the Shi’ite community was forbidden to hold collective prayers and other ceremonies in the Moscow Grand Mosque. Since then, they have been removed from the mosques of Moscow, which are controlled by the official state Muslim authorities.

In an incident in 2016, Sunni authorities offered them to pray on the premises of the Iranian Cultural Center at the Iranian embassy.8 All complaints sent to the mayor’s office of Moscow and even to Putin were in vain. They were even thrown out of mosques which were built with Shi’ite donations. In early 2017, the leader of the Chechnya region and a Putin favorite, Ramzan Kadyrov, went even further by completely banning Shi’ite rites.

Moreover, the security services began to show an interest in the activities of the Ahli Beit. For example, in October 2019, police officers from Unit E (that combats extremism) interrupted Friday prayers in the Ahli Beit branch of St. Petersburg. Ultimately, no evidence of extremism was found, but the organization was fined for violating the law regarding missionary activity. This demonstrates that Russian authorities do not perceive Shi’ite Islam as an indigenous religion of Russia.

During these incidents, the leaders of the Shi’ite community behaved quite reservedly. They did not complain publicly and did not threaten the official Sunni Authorities of Russia. Perhaps this restrained behavior can be explained by their reluctance to draw additional attention to its activities.

In January 2022, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi made an official visit to Moscow and gave a sermon at the Moscow Grand Mosque.9 However, it is still unclear whether this visit will change the attitude towards the Shi’ite community and whether they will be allowed to hold public prayers in the future.

Yet, the spread of Shi’ite Islam in Russia has not stopped. There are growing Shi’ite communities in more than a dozen large cities across Russia, but not all of them are affiliated with the Iranian agenda. Two comprehensive websites promote conversion to Shi’ite Islam and deal exclusively with spiritual issues with no connection to contemporary politics. Moreover, the websites promote a very moderate and peaceful version of Shi’ite Islam, stressing that any “uprising” is illegitimate until the arrival of Imam Mahdi (the Messiah in Shi’ite Islam). This shows that Ahli Beit has restrained itself compared to its activities in the past.

Several prominent Shi’ite activists from different regions of Russia and with different ethnic origins took part in an event at the Iranian embassy in Moscow in December 2020. The event was in honor of the anniversary of the assassination of Qassem Soleimani, the former leader of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards.

Among the attendees were Anastasia Fatima Yezhova, an ethnic Russian convert to Shi’ite Islam; radical anti-Semitic Sunni Mufti Nafigullah Ashirov, considered to be an opponent to Russia’s mainstream Muslim authorities; a representative of Dagestan’s Shi’ites, Nuri Mohammadzadeh; and finally, one of the leaders of Central Asia’s labor migrants in Russia, Mais Gurbanov.

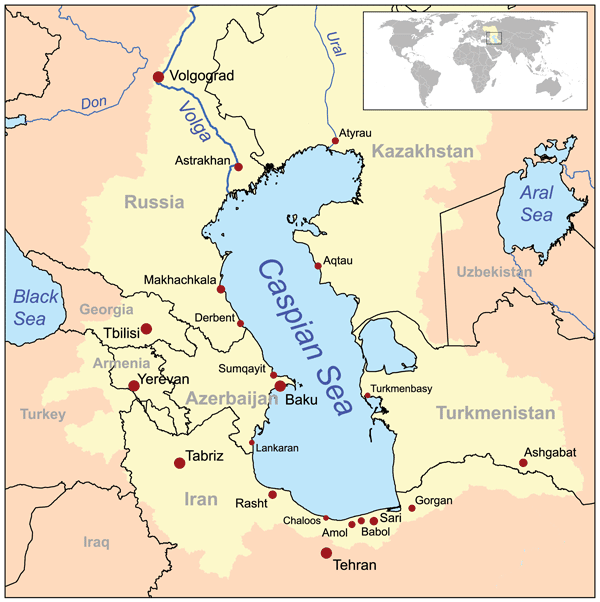

Iranian Impact Beyond Moscow

There are two official Iranian representatives outside Moscow. One in Kazan, the capital of the Republic of Tatarstan, and Astrakhan, the center of the eponymous district. Kazan is the capital of the most developed among the Russian regions, which have a predominantly Muslim population (6th -7th among Russia’s regions by GDP). Astrakhan is one of the two main cities on the Caspian Sea. Iran faces difficulties expanding its influence in the Makhachkala port city (its second Caspian city in Dagestan). Iran had hoped to use it as a foothold to expand its influence in Russia’s Caucasus region. (See Map below).

At the beginning of 2016, the Russian government approved a green corridor to facilitate customs between Dagestan and Iran, which was supposed to increase trade through Makhachkala. Yet, in 2017 the trade decreased significantly. There were a few causes: competition with different Russian economic groups in the North Caucasus and the uncertainty of the future status of the port of Makhachkala if it would be state-owned or privatized. In addition, in recent years, several high-profile criminal scandals have been associated with this port.

The failure to use the port of Makhachkala led to more use of the Astrakhan port. In 2016, at least 200 Iranian commercial companies were represented in the city of Astrakhan. This reflects the Iranian preference to redirect a more significant part of their trade and their influence to Dagestan and the Muslim Northern Caucasus.

Jamal Aliyev, deputy general director of the port of Makhachkala, consistently argues in the media about the need to remove obstacles from trade with Iran. This coincides with his professional duty and interests. In the past, Aliyev twice headed the offices of Russian companies in Iran. In particular, the commercial representative office of the port of Makhachkala in Iran from 2011 to 2015. Aliyev, a lawyer, combines his work in the port with the position of Ombudsman for Human Rights of the Republic of Dagestan, which increases his immunity from scrutiny.

Strong Iranian Presence in Universities in the Periphery of Russia

Iranian activity across Russia is also characterized by close cooperation with local universities. Wherever centers of Iranian culture are opened, students are invited to study the Persian language in Iran.

The scope of these activities is enormous, and it is difficult to accurately evaluate them in this study. For example, at the annual meeting between the Iranian ambassador and Persian language teachers in 2019, more than 100 teachers from Russia took part.10 Some of the major universities whose research centers or faculties maintain close contact with the Iranians are: St. Peterburg State University, Federal University of Kazan (Tatarstan), Academy of Science of Tatarstan, Astrakhan State University, Ural Federal University located in Yekaterinburg (third-largest city), and the Siberian Institute of International Relations and Regional Studies in Novosibirsk. Many of these universities also have departments dedicated to Iranian studies.

The cooperation programs usually include travel grants, scholarships, visiting teachers, and lecturers from Iran. Among the institutions mentioned above, St. Peterburg State University is the most important for Iran. In 2019, its rector received a special award from the Iranian ambassador for promoting Iranian studies in Russia.11

Specifically in the region of North Caucasus, these contacts are used by Iranians to thoroughly learn and create networks and allow them to improve their knowledge of the key languages of the North Caucasian republics, which are necessary to act effectively in the region. In addition to promoting a positive image of Iran, its emissaries manage campaigns against Turkish influence in the region by supporting the Iranian historical narrative of a “good Persian” and “bad Turkish” influence and intervention in the Caucasus. For example, The Center of Iranian Culture in the North Ossetian State University carries out Iranian activity in the North Caucasus.

Iranian “wallets” in Russia?

Lobbying is an expensive effort. Since 2012, there have been several attempts by Iranian entities to be involved in the activities of several Russian banks. These attempts failed from 2014 to 2017. In 2014, the license of Ogni Moskvy (Lights of Moscow) bank was canceled amid an effort by Iranian investors to take over the bank and invest up to half a billion dollars in it.

In April 2016, the license of the First Czech-Russian Bank was canceled. The bank’s name is misleading because Czechs were only involved in its founding. Later, the controlling stake was bought out by a prominent Russian business. Then, in 2014, 1,6 billion Rubles (about $24 million) were invested in the bank by the Iranian State Bank, with additional investments expected. However, in 2016, the bank was closed. Nothing is known about reimbursements for the Iranian state investors. In addition, the bank’s subsidiary in the Czech Republic had been previously closed by local authorities on charges of money laundering and participation in the financing of terror.

Finally, in 2017 the license of Tempbank was canceled. The bank was affiliated with Iranian and Syrian companies and their offshore entities in Cyprus. Officially, the revocation of its license was due to gross violations of the law, embezzlement, and theft.

Iran’s financial investments in Russia are allowed only through the Mir Business Bank – a subsidiary of Bank Melli Iran, which is controlled by the Iranian regime. This is the only bank in Russia allowing money transfers to Iran. As one could expect, in addition to the main office in Moscow, this bank has branches in Kazan and Astrakhan, where Iranian consulates are located.

The failure of Iranian attempts to organize a banking infrastructure in Russia is likely due to Russian fears of the effects of sanctions against Iran. Restrictions on Iranian banking activities by the Russians also reflect security concerns.

Conclusion

Iran has aggressively promoted its influence in Russia, particularly in academia. It has long-term aims to influence future generations of leaders and Russian Middle Eastern experts. The prevalence of the Iranian narrative in the Russian media comes at the expense of the Israeli position. Ideally, for Iran, its efforts could result in closer cooperation.

Since 2016, Iranian efforts in Russia have been significantly hampered. This is surprising given the growing tension between Russia and the West and the seemingly growing dependence on countries such as Iran. However, the Iranians have failed in their anti-Israel agenda as Russia continues its cooperation with Israel in Syria.

Russia is also balancing between Iran and maintaining its relations with Sunni Arab states. Moscow prefers the active participation of Sunnis in the post-war reconstruction of Syria.

Today, Iran has no lobbyists among Putin’s senior aides. Even the trade between Moscow and Tehran is growing slowly. Most Iranian achievements in Moscow should be attributed primarily to the growing confrontation between Russia and the West and not the result of successful Iranian lobbying.

Russian attitudes towards Iranian activities in their country may have been influenced by close cooperation in Syria since 2015. However, there are significant disagreements with the Iranians over Syria, spheres of influence in the Caspian region, and the Southern Caucasus.

Because of the growing tensions between Russia and the West, Iranian influence in Russia should be expected to increase, making it more difficult for Israel and its relations with Moscow.

However, Israel should not ignore Iran’s growing influence in Russia. A promising path could be the growing cooperation with Israel’s new partners of the Abraham Accords and Turkey and Saudi Arabia. All these actors are against Iran gaining influence in Russia. Nevertheless, even if there were a complete rupture between Russia and the West, Israel could achieve significant results by cooperating with like-minded Sunni actors.

[1] Hale, Henry E. (2014) Patronal Politics: Eurasian Regime Dynamics in Comparative Perspective. Cambride University Press. Pp.422-454

[2] https://www.rbc.ru/spb_sz/27/02/2010/559290da9a79477444af62a8?from=materials_on_subject

[3] https://vestikavkaza.ru/news/Strany-TSAK-vyrabotali-v-Tegerane-strategiyu-po-borbe-s-narkotikami.html

[4] Putin’s ruling party is increasingly pushing any political alternatives to the margins of political life. A consequence of this is that it is turning even the most loyal and tamed opposition into a real one.

[5] https://russia.mfa.gov.ir/ru/newsview/618568

[6] https://www.rsuh.ru/en/faculties-departments-and-international-centers/russian-iranian-center/

[7] Dina Lisnyansky. (2009) “Tashayu (Conversion to Shiism) in Central Asia and Russia”, Hudson Institute: Current Trends in Islamist Ideology, June 23, 2009 [https://www.hudson.org/research/9843-tashayu-conversion-to-shiism-in-central-asia-and-russia- ]

[8] https://islamnews.ru/omon-pribyl-v-sobornuyu-mechet-moskvy-raznimat-musulman

[9] https://russian.rt.com/opinion/953332-yuzik-iran-prezident-raisi-rossiya-vizit-reakciya

[10] https://parstoday.com/ru/news/russia-i108403

[11] https://spbu.ru/news-events/novosti/posol-irana-poblagodaril-spbgu-za-vklad-v-prodvizhenie-iranistiki

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.