By

When Israel declares sovereignty in the Jordan Valley and the Jerusalem Envelope, this must be accompanied by significant economic development and construction.

Introduction

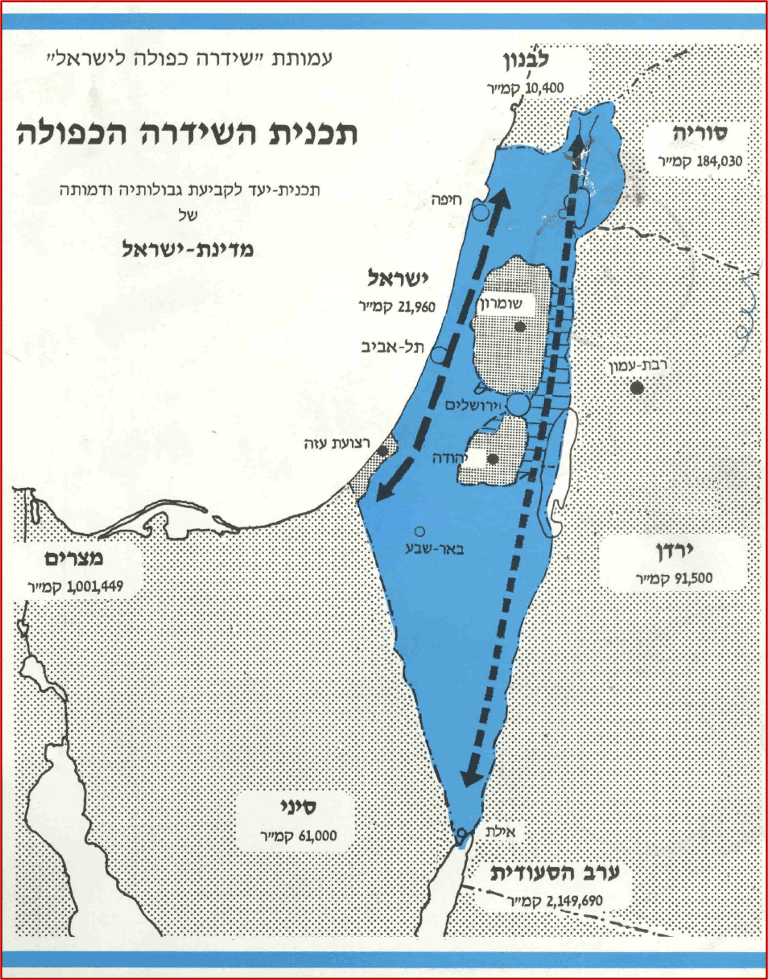

The planned (but delayed) application of Israeli sovereignty in the Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea coast (the “Eastern Strip”) was intended to physically separate the Kingdom of Jordan from the Palestinians of Judea and Samaria, and to prevent a security threat to the State of Israel in the event of Palestinian statehood. The application of Israel’s sovereignty in the Jerusalem Envelope was intended to expand the space of the capital city and to create a significant West-East corridor via Jerusalem that ties Israel’s “Western Strip” (along the Mediterranean coast) to its “Eastern Strip.” When Israel declares sovereignty in the Jordan Valley and the Jerusalem Envelope, this must be accompanied by significant economic development and construction.

This paper proposes a plan to economically develop Israel’s “Eastern Strip.” This is the optimal way to deal with the current dangerous reality, in which 70 percent of Israelis live in the Jerusalem-Haifa-Ashdod triangle and 80 percent of Israel’s physical and economic infrastructure similarly is concentrated there too.

Population dispersal is currently one of the most important national missions. However, it is not possible to move the population eastward without creating new and attractive jobs in the Eastern Strip. This plan suggests large-scale national projects that will improve the infrastructure of the State of Israel and fulfil national goals. The projects relate to tourism, agriculture, and transportation, and will lead to the creation of tens of thousands of new jobs, economic growth and prosperity.

This framework also will address several basic problems, including: 1. The need to stop decline in Dead Sea water levels and damage to its surroundings, 2. The shortage of irrigation water for agricultural development in the Jordan Valley, 3. The need for a new international airport in the center of the country (in addition to Ben-Gurion Airport), and 4. The need to expand the Jerusalem metropolitan area.

To solve these problems, the plan proposes 1. To build a Mediterranean-Dead Sea Canal along the Palmachim-Qumran route, together with a desalination plant and a hydroelectric power station along this canal, 2. To construct a new international airport in the Horqania Valley in the Judean Desert, and 3. To expand the Jerusalem metropolis eastwards.

Transportation will be developed by constructing a high-speed train from the new international airport in the Horqania Valley to central Jerusalem (15-minutes commute) and by paving highways that will connect Jerusalem to the Eastern Strip, to Route 90 (from Metula to Eilat along the Syro-African rift) and to its parallel Route 80 (Alon Road from Arad to Mnt. Gilboa).

Tourism will be developed by building new clusters of hotels and visitor centers on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea (which will cease to recede), and establishing parks, heritage sites and nature reserves in the lowest place on Earth.

Agriculture will be developed on an area of hundreds of thousands of dunams in the Horqania Valley and in the Jordan Valley, and irrigation water will be supplied from the huge desalination facility that will be built as an integral part of the Mediterranean-Dead Sea Canal.

The development of transportation, tourism and agriculture in the Jerusalem Envelopeand in the Eastern Strip will lead to the development of rural and urban settlement in the area, as well.

The construction of the Mediterranean-Dead Sea Canal (the “Seas Canal”) and the development of transport, tourism and agriculture along the Eastern Strip will also strengthen the peace with the Kingdom of Jordan, in three ways. First, the State of Israel will be able to sell water to Jordan in whatever quantity it wishes. Second, the new employment centers will provide jobs for Jordanian workers. Third, stabilizing Dead Sea levels also will enable the development of tourism on the eastern (Jordanian) coast of the Dead Sea.

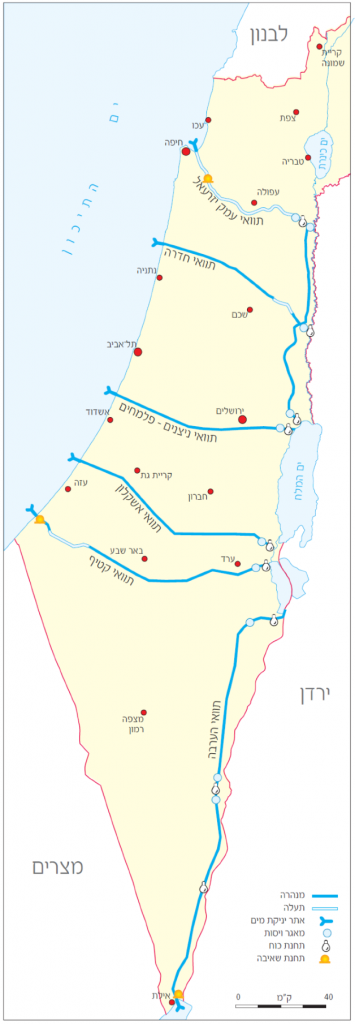

The Med-Dead Canal Along the Palmachim-Qumran Route

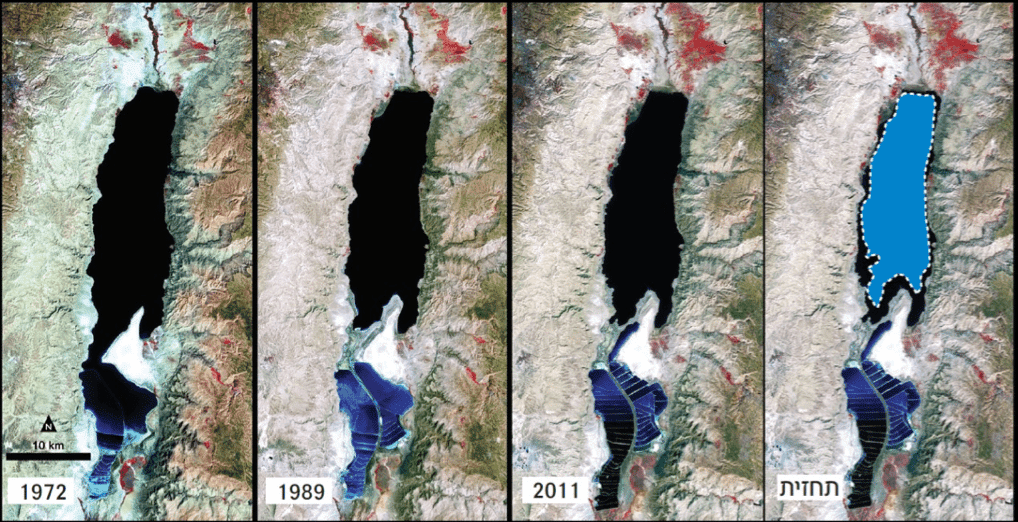

The Dead Sea is drying-up due to increased consumption of water from its tributaries throughout the watershed (Israel, Syria, Lebanon and Jordan). Its level has dropped from -390 meters (below sea level) in the early twentieth century to -434 meters today. The current rate of decline is about 1.1 meters per year. The dropping level of the lake accelerates sinkhole formation and stream incision along the narrow coastal plain; thereby damaging the infrastructure of roads, agriculture and tourism on the shores of the Dead Sea.

Stopping the depletion of the Dead Sea is possible by building a Mediterranean Sea to Dead Sea Canal (the Med-Dead Canal) that will transfer seawater to the lake, in such a way that its level will be stabilized so that it remains at a constant height and does not deteriorate.

To date, the Med-Dead Canal has not been constructed for three reasons. First, because of concern over its environmental effects, and especially the dangers of gypsum crystal settling (due to the mixing two water types) and algae (dunaliela) blooms. Second, the Israeli government has preferred, for the sake of peace with the Kingdom of Jordan, to consider a “Seas Canal” on a southern route, from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea at Sodom, in the territory of the Kingdom of Jordan. Unfortunately, in practice, the Jordan has failed to advance the plan, mainly due to the high economic cost of the 230-km-long southern route. Third, the most economically feasible alternative, from Palmachim to Qumran, has not been considered because of the need for agreement and cooperation with the Palestinian Authority (PA).

However, applying Israeli sovereignty to the Jordan Valley and Jerusalem Envelope will end this deadlock and change the reality. First, the application of sovereignty will allow the construction of a Med-Dead Canal without need for cooperation with the PA. Second, economic evaluations show that a canal along the short 70-km-long central route, Palmachim-Qumran, is the most economically viable. Third, recent studies show that the environmental hazards of this route will be mitigated. All the economic-engineering-environmental analyses indicate the high viability of the canal on the central route.

If the water discharge to the Dead Sea exceeds 700 million cubic meters per year (mcmy), the Dead Sea will become a stratified lake, with the upper layer composed of seawater (or the residual brine after desalination) and the lower layer composed of the original Dead Sea water. The gypsum crystallization will then occur at the boundary between the layers and not on the water surface, so that no environmental damage will be created. Beyond that, the chances of algae blooming are particularly high in the northern route (due to the drainage of agricultural fertilizers from the Sea of Galilee basin, and thereby the supply of phosphorus), but they are low in the central route, Palmachim-Qumran. It is therefore advisable to construct the canal along the central route.

This canal plan includes the construction of a desalination plant in the Horqania Valley. The canal will transfer 1,800 mcmy of Mediterranean seawater, of which 800 mcmy will be desalinated. The desalination plant will be built in four phases, amounting to 200 mcmy in each phase, according to the time-schedule of demand expansion. At the first stage, all the seawater will flow into the lake, and then, as the desalination facilities are built, the flow of ordinary seawater to the lake will decrease and the flow of residual brine after desalination will increase. The flow to the Dead Sea will begin at 1,800 mcmy, which will partially raise the lake level, and the flow will gradually decrease to 1,000 mcmy, and this value will remain constant so that the lake level stabilizes. The flow of seawater and / or residual brine (after desalination) from the Horqania Valley to the Dead Sea, across a height difference of 400 meters, will make it possible to build a hydroelectric power plant for electricity generation on Qumran cliff.

Tourism Development Along the Dead Sea Coast

The Dead Sea is the lowest place on Earth, and it attracts great international attention. The tourist attractions around the Dead Sea are plentiful, including: the canyons in the Judean Desert, the sweet and salty springs, archeological sites, heritage sites for different religions, medical tourism, dry and hot climate, and unique geomorphological phenomena (sinkhole opening and stream incision). In fact, the Dead Sea was nominated for one of the Seven Wonders of the World (but failed in the international competition for political reasons).

Unfortunately, despite the enormous potential for tourism (by any international standards), the actual scope of tourism is very limited. In fact, just one cluster of hotels has been built on the shores of the evaporation ponds of the Dead Sea Works (Ein Bokek and Neve Zohar). Tourist potential cannot be realized because of the continuing decline of Dead Sea levels and the constant retreat of the coastline.

Stabilizing the Dead Sea level at a fixed height will make it possible to build hotels on the lakeshore with a guaranteed future, since the shoreline will stop receding. Stabilizing the lake level will stop stream incision since the drainage base will stop dropping. Stabilization of the level will enable the construction of permanent infrastructures for transportation, tourism, and agriculture on the lakeshore. Stabilizing the sea level will also make it possible to establish a geological park for sinkhole tourism on the lakeshore.

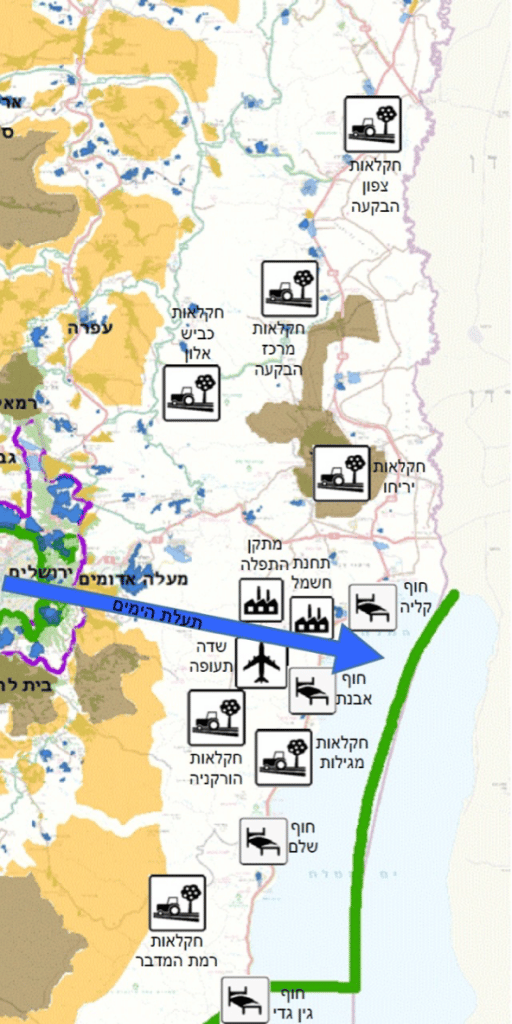

Consequently, it will be possible to establish new hotels and tourist centers on the alluvial fans of the large streams: Kalia Beach atop of the Qumran River Fan, Avnat Beach atop of the Kidron River Fan, Shalem Beach atop of the Darga River Fan, and Ein Gedi Beach atop of the Arugot River Fan. In the tourist centers, it will be possible to build hotels, shopping centers, visitor centers and campsites at various levels, thereby allowing access to nature reserves and heritage sites. In addition, it will be possible to open a geological park for sinkhole tourism and hidden canyons. The geological park will allow observation of unique morphological processes that had accompanied the decline in the lake level, and by itself it will attract international attention.

Horqania Valley International Airport

Ben-Gurion International Airport is unable to handle the future volume of air transportation to the State of Israel. The population increase in Israel (expected to reach 15 million people by 2050), and especially in the large urban centers of Jerusalem and the Dan region (greater Tel Aviv), necessitates the construction of another new international airport in the center of the country. In recent years, four million tourists have visited Israel each year, and about a third of them stay in Jerusalem. There is no doubt that Jerusalem needs an international airport. The small Atarot airport which operated in northern Jerusalem has long been closed. A new and modern airport is needed for the capital.

The two plans currently on the table for the establishment of airports in the Galilee and in the Negev are of great importance for the development of the northern and southern parts of the country. But they are not suitable for the development of air transportation to/from the center of the country.

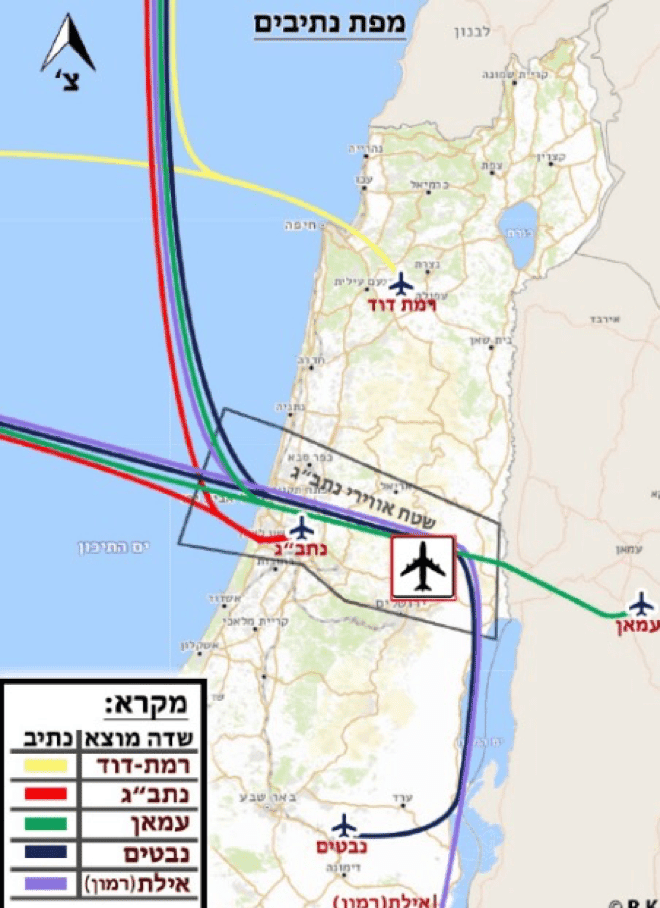

The optimal solution is building a new international airport for Jerusalem, with a 15-minute-comuting-time into the city. This could be in the Horqania Valley, in the Judean Desert. The Horqania Valley is a flat area, 10 km long and 5 km wide. The area is not populated, allowing for the construction of two parallel runways (for landing and taking-off) similar to modern airports around the world. The area is currently used as an IDF training zone, which would have to be relocated. The Horqania Valley is located along the existing international air-route (from Eilat to Ben Gurion Airport), eliminating the need to open a new air-route. This airport will not interfere with Israel Air Force operations, which are restricted mainly to the area south of Palmachim.

Ground Transportation from Horqania to Jerusalem

The proposed Jerusalem International Airport will be connected to the city of Jerusalem by both trains and roads. The inter-city train from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem can be extended to the airport in Horqania, with several stops in the city center (linking to municipal transportation) and with another stop in Maaleh Adumim. The train ride time from Horqania to the city center will be about one quarter of an hour. The airport will also be connected via an interchange to Route 1, between Jerusalem and Jericho.

Ground transportation from Horqania will be integrated with the main highways of the State of Israel, to Route 90 (from Metula to Eilat along the Syro-African rift) and its parallel Route 80 (Alon Road from Arad to Gilboa), and to Route 1, from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and Jericho (and in the future to Amman in the Kingdom of Jordan).

Horqania Desalination Plant and Qumran Hydroelectric Power Station

A desalination facility will be built as an integral part of the Seas Canal. As stated above, the plant will be built in four phases, depending on the increase in water demand. Each of the four phases will desalinate 200 mcmy and at the end of the process 800 mcmy will be desalinated. The desalination technology will be based on reverse osmosis, in accordance with the extensive experience accumulated in the desalination facilities established by Israel in recent years along the Mediterranean coast. The desalinated water will be supplied for three purposes: for the development of new settlement, new agriculture, and export to the Kingdom of Jordan.

The waters of the Mediterranean Sea and/or the residual brine after desalination will be transferred into the Dead Sea across the cliff at Qumran. The height difference of 400 meters can be used to generate hydroelectric power with an annual amount of 2-3 billion kWh.

Agricultural Development

The Judean Desert includes wide valleys and flat areas that have the potential for developing intensive agriculture. The Horqania Valley is the largest potential area, 10 km long and 5 km wide. Around the airport and around the facilities of the canal, the desalination plant, and the power station, it will be possible to grow agricultural crops typical of the desert climate, and especially date palm groves of the Majhool variety. Farmers in Jordan Valley settlements have amassed a great deal of knowledge about growing dates. Their products are marketed profitably both in Israel and around the world.

Agriculture in the Jordan Valley is currently based on irrigation water of three types: fresh groundwater from local wells, sewage effluents produced from Jerusalem waste-water treatment plants, and brackish water from the Jordan River and floods. Eastern Jerusalem wastewater is currently treated at the Nabi Musa sewage treatment plant and is stored in the Jordan Valley in the Tirza reservoirs, together with local flood water. Irrigation in the future will be developed based on desalinated water, whose quality is equal to that of well water, and on the sewage effluents of Jerusalem and other settlements at the mountains. Effluent irrigation is an optimal solution for eliminating the sanitary trouble of sewage and for creating an additional water source for agriculture.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture, it is already possible to double the agricultural areas in the existing settlements in the Jordan Valley, on the Dead Sea shore and along the Alon Road. Of course, additional agricultural areas can be added in the Horqania Valley, along the Alon Road, and in the plateau across the Judean Desert towards Arad. Through the desalinated water and the effluent water, it will be possible to cultivate hundreds of thousands of new dunams of agriculture and to irrigate them with hundreds of mcmy. The demand for irrigated water also exists among the Palestinians in Jericho, and it will be possible to provide them with as much water as they require, too.

Urban Development

The metropolitan area of Jerusalem needs to expand. However, expansion of the city westwards has been stymied because of protected green spaces. Expansion of the city eastwards towards Maaleh Adumim is an ideal solution for families who want to maintain daily contact with the city, but here too expansion has been stymied for political reasons, and in any case, the land reserves are limited.

The application of Israeli sovereignty in the Jerusalem Envelope further eastwards will allow for growth in the Alon – Nofei Prat – Kfar Adumim area, the Mitzpe Jericho area, the Almon – Geva Binyamin – Mikhmas area, and the Kedar area.

The development of transportation, tourism and agriculture will make it possible to create tens of thousands of new jobs. The new workers will live in new urban and rural communities to be established in this area. The new settlements will create a continuum from Jerusalem through Maaleh Adumim – to the Horqania Valley, the Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea shore. The metropolis of Jerusalem will be expanded to connect to the Eastern Strip of the State of Israel.

Summary

There is a broad Israeli consensus about the importance of incorporating the Jordan Valley and the Jerusalem Envelope into Israel because of national security considerations; and this area does not burden the Jewish State with demographic problems. But the application of Israeli sovereignty to the Eastern Strip and the Jerusalem Envelope is important not only for strategic reasons, but also for the sake of large-scale economic development, including major national infrastructure projects as detailed above and summarized below:

- Med-Dead Sea Canal along the Palmachim-Qumran route

- Horqania desalination plant and Qumran hydroelectric power station

- Intensive agriculture in the Horqania Valley and the Jordan Valley

- Hotels and tourist centers on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea

- Jerusalem International Airport in the Horqania Valley

- High-speed train and swift highway from the airport to Jerusalem

- Continuous settlement in an arc from Jerusalem to the Dead Sea and the Jordan Valley

These projects can only be implemented after the application of the State of Israel’s sovereignty over the Jordan Valley, the Dead Sea shore and the Jerusalem Envelope. Without sovereignty, it will not be possible to implement the projects due to the need for the consent of the Palestinian Authority – which will probably not cooperate, alas.

A plan of this magnitude requires careful and complex master planning, detailed scheduling, major budgeting across many government ministries (including finance, justice, interior, transportation, tourism, agriculture, infrastructure, environmental protection, etc.). International tenders must be published, land must be allocated, and cooperation initiated between the private and government sectors. Coordination of this magnitude requires leadership of the Prime Minister’s Office.

Haim Gvirtzman is a professor at the Institute of Earth Sciences at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

First published by the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security, 02.09.2020