- His Charisma Was Unique, But No Match For Egypt’s Chronic Problems, better tackled by Sadat’s Strategy

By Amir Oren

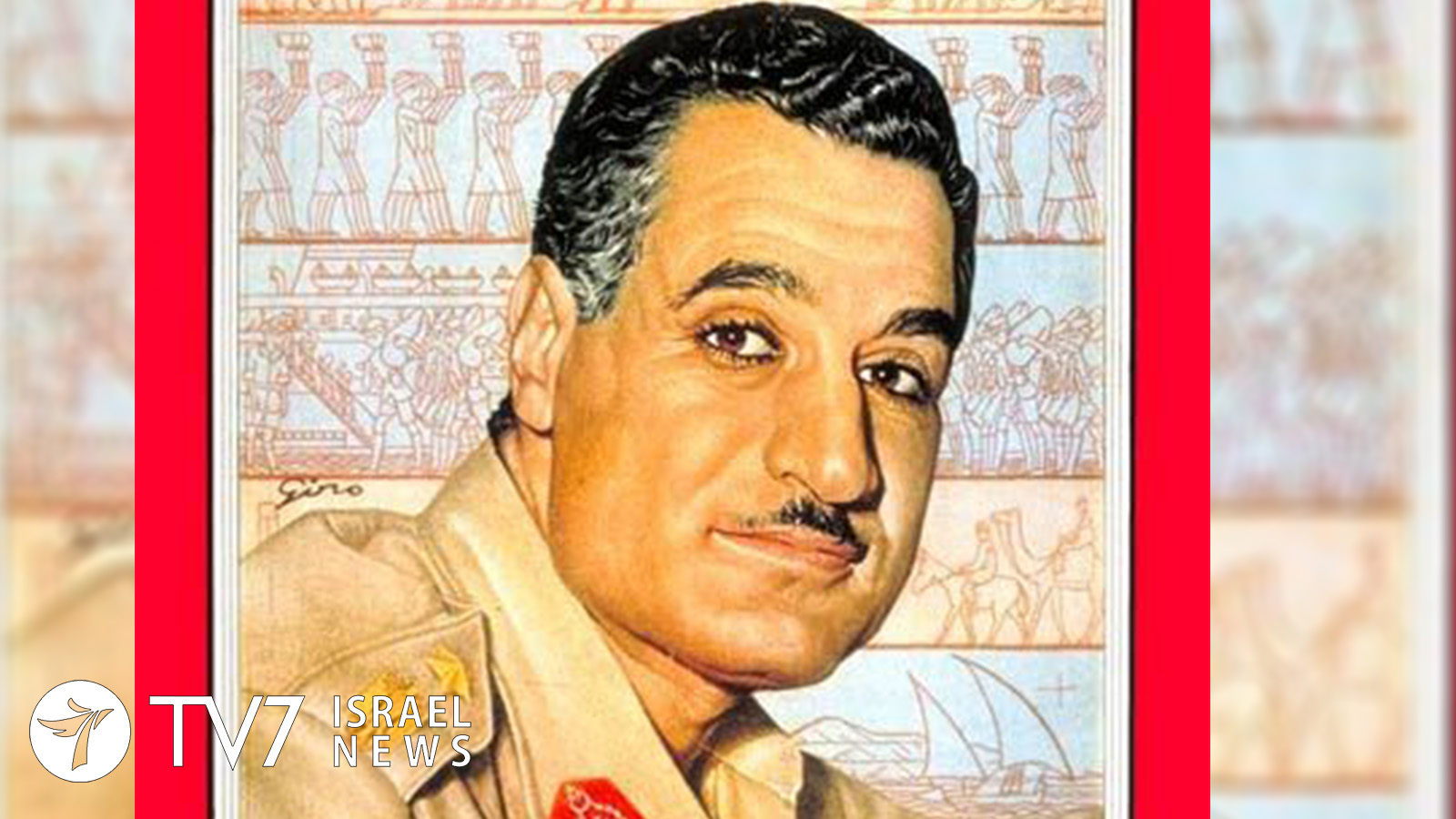

Gamal Abdel Nasser died 50 years ago, on September 28, 1970. His ailing heart failed in mid-mediation between Jordan’s King Hussein and FATAH’s Yasser Arafat. It was a shocking end to what Palestinians called “Black September”, when they skyjacked Western airliners to a Jordanian airfield, blew them up, challenged Hussein and were beaten when Israel and the U.S. threatened to intervene and an armored Syrian force was repulsed.

In the five decades since Nasser’s death, no-one in the Arab world emerged to take his place. Many tried to emulate him, but neither Saddam Hussein nor Muammar Gaddafi came close. His charisma and mass appeal were inimitable. There may never be another Nasser – times and mass media have changed.

Yet today Nasser is largely forgotten, as his policies did not pass the test of time. The officers-turned-politicians who inherited his mantle wisely chose to focus on Egypt’s core problems, putting aside Nasser’s grand designs of being at the center of three rings – Arab, Moslem and African, as befits Egypt’s unique position – and opting for peace with Israel. Nasser took his country out of the deep hole it sank into in the early 1950’s, but eventually led it into a dead end, out of which his underappreciated deputy Anwar Sadat extricated it, courageously paying with his life.

At death, Nasser was only 52, having been Prime Minister and then President since before he turned 35. In a decade and a half, he was the dominant force – and face – of the Arab Middle East, much like his nemesis Moshe Dayan became the icon of the Israeli Defense Forces which defeated him in 1956 and 1967 and arguably in the 1969-70 War of Attrition, if one considers the belligerents’ aims and not only the costs.

His Free Officers group, where he wisely left center stage at first to a senior General recruited for respectability, was not the first one to topple a government in a military coup following the debacle of the 1948 invasion of Israel and the Palestinian state which was never established. Syrian Colonel Hosni Zaim claimed that honor when he launched the series of coups in Damascus and soon fell victim to the next one. But Nasser, Sadat and their fellow officers were the most successful. Except for Mohammad Morsi’s brief reign, Nasser’s regime is essentially still there, with Hosni Mubarak and now Abdel Fatah a-Sisi in the role of a Pharaoh out of uniform.

The revolution – and indeed, it turned out to be more than a coup, sweeping aside not only the corrupt Farouk monarchy but also the old regime’s parties and politicians – had some initial successes, such as forcing the British to evacuate their Suez Canal bases. But in employing Palestinian terrorists against Israel and helping Algerian rebels against France, he brought about the secret “Musketeer” alliance against him. Rather than oust him, the British and French Prime Ministers were soon out themselves, as the U.S. refused to back them, but the Israeli military distinguished itself in planning and fighting, deterring Nasser from direct confrontation for an entire decade.

Meanwhile, Nasser enjoyed his relationship with the Moscow – in return for weapons the West would not sell him, he let the Soviets leapfrog over the “Northern Tier” of Iraq, Iran and Turkey and penetrate the Middle East. He became a leader of the Non-Aligned movement, which portrayed itself as neutral but was more anti-American than anti-Soviet. In his own region he kept trying to subvert pro-Western regimes, especially the Kingdoms. In Yemen, his expeditionary corps found a quagmire he could neither help win nor withdraw from. For a couple of years he presided over a union imposed on Syria, but was surprised and shamed by a rebellion which left the name United Arab Republic an empty shell.

Usually more cautious than his military chief and fellow Free Officer Abdel Hakim Amer, Nasser became captive to his own bravado in May 1967, when goaded by Syrian, Soviet and UN moves and a hesitant Eshkol government in Jerusalem he challenged Israel to take him – and Syria, and Jordan – on. The Six-Day War which ensued made Nasser the face of defeat. He resigned, whether sincerely or tactically, stayed in office by popular request, and purged the armed forces in order to prepare for another round, but he was no longer the Nasser of his 30’s and 40’s.

In the age of Television and internet, one can hardly recreate the magnetic appeal Nasser had over the radio for Arab masses at home and abroad. Rulers had reason to fear that he could turn their “Arab streets” against them. There were and still are basic factors working against a Pan-Arab union, but if there was ever a chance for a single leader to make it happen, it was Nasser.

In choosing his different path, slowly and carefully working his way towards the American orbit so as to open up Egypt’s failing economy and feed and educate the exploding population, Sadat made sure to pay his respects to Nasser. On his third anniversary, September 28, 1973, Sadat publicly promised that occupied Sinai will soon be liberated. On the same day Soviet Foreign Minister Gromyko warned President Nixon and Secretary of State Kissinger that “we could all soon wake up to war”. In Israel, it was the day after Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, and attention was focused elsewhere, if at all. A week later, the Yom Kippur War was launched, leading to gradual peace talks and Sinai’s return. The gray, unimpressive Sadat has succeeded where the charismatic Nasser did not.